A citizen wave to reclaim public and democratic water in Catalan municipalities

April 5, 2018 | Míriam Planas

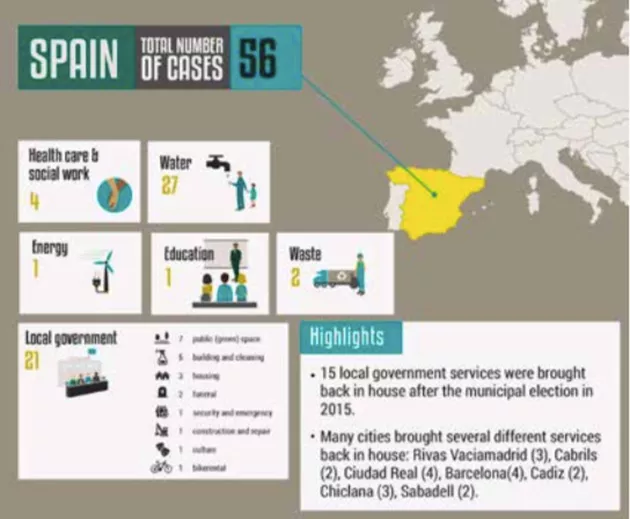

Catalonia experienced its first remunicipalisation of water in 2010, in the town of Figaro. Seven years later the door of remunicipalisation (or municipalisation considering that water was never publicly managed in some places) is now wide open and an estimated 3.5 million of the 7 million inhabitants in Catalonia, including Barcelonans, could see a change to their water management model during the coming years. This is an opportunity to advance management of water as a common good, in a more democratic way that guarantees the right to water for all, ensuring the most basic needs of the people and the preservation of water ecosystems. The water remunicipalisation trend in Catalonia is part of a wider trend throughout Spain, which continues in spite of the conservative central government’s every efforts to hinder it. The Agbar quasi monopoly in Catalonia Private companies supply water to 83.6 per cent of the Catalan population. The Agbar Group (Aguas de Barcelona), now a subsidiary of the French multinational Suez, services 70 per cent of the population, that is, 5.6 million inhabitants. Additionally, nearly 0.5 million people get their water from Aqualia, a subsidiary of the Spanish construction company FCC (Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas). At the national level, roughly 57 per cent of the Spanish population gets its water from a private provider. Agbar, which is headquartered in Barcelona, is by far the dominant player in the Spanish market. Historically Barcelona and Catalonia have thus formed the bastion of private water management in the country.

The Agbar quasi monopoly in Catalonia

Private companies supply water to 83.6 per cent of the Catalan popu- lation. The Agbar Group (Aguas de Barcelona), now a subsidiary of the French multinational Suez, services 70 per cent of the population, that is, 5.6 million inhabitants. Additionally, nearly 0.5 million people get their water from Aqualia, a subsidiary of the Spanish construction company FCC (Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas). At the national level, roughly 57 per cent of the Spanish population gets its water from a private pro- vider. Agbar, which is headquartered in Barcelona, is by far the dominant player in the Spanish market. Historically Barcelona and Catalonia have thus formed the bastion of private water management in the country.

In Catalonia, the private sector is concentrated in medium and large cities because larger populations offer better return on investment. Elsewhere there is a long tradition of public management, with 450 small munici- palities being serviced by public water utilities – that is, half of the mu- nicipalities of Catalonia but only 16.4 per cent of the population.

According to a report of the Spanish Court of Accounts in 2011,1 private water management is 22 per cent more expensive for small and medium towns than public provision, while offering a lower performance on av- erage. Catalan average water prices in privately managed municipalities are 25 per cent higher than in municipalities with public management. In Barcelona’s metropolitan area (includes 22 surrounding municipalities), the Aigua és Vida platform estimates that Agbar’s water rates are 91.7 per cent more expensive than in neighbouring towns such as El Prat de Llo- bregat and Barbera, which have public management.

The situation of water provision in Catalonia may be about to change radically, however, considering that 14 Catalan towns have already mu- nicipalised or remunicipalised their water. Concession contracts in some 90 more municipalities – home to about 3.5 million people – are set to expire in the coming years (2017-2025, see Appendix). Many of the pri- vate contracts in force today have not gone through a proper tendering process. Dozens of town councils have already approved the study of (re) municipalisation scenarios for water provision. Along with the vibrant citizen mobilisations and platforms for reclaiming public and democratic water in Catalonia and the whole of Spain, this has resulted in the current wave of (re)municipalisation.

Change of scenario: The (re)municipalisation wave

In 2015, citizen-led, progressive coalitions gained power in many Span- ish cities, including Madrid and Barcelona. This was the result of years of citizen movement campaigning for access to basic rights and against the corruption of traditional political parties and their close connections to big business. In turn, it created a favourable political environment for remunicipalisation. Valladolid (300,000 inhabitants) is the largest city to have remunicipalised water services in Spain.2 The municipal council has decided to return water management to public hands when the con- tract with Agbar expires, in July 2017. Although it does not fall within the scope of this chapter, it must be noted that many of these municipalities (which are not necessarily driven by progressive coalitions) embarked on remunicipalising not only water, but other services as well. An im- portant obstacle, however, is the central government, which is trying to make it impossible for cities to remunicipalise public services. In April 2017, the central government presented a draft budget proposal that in- cluded an additional disposition (no. 27) that was cause for concern for many but that was not adopted as proposed.3 It would have prevented the transfer of those workers previously in the private sector into any new public body, with the underlying objective of turning unions and workers against remunicipalisation. This would have led to a loss of expertise and created a lack of skilled workers to provide the services. The central gov- ernment also has directly fought against remunicipalisation in Valladolid. In March 2017, the Ministry of Finance through the State Attorney’s Of- fice filed a lawsuit4 to block the staff’s transfer from the private company to a new public company, invoking budgetary adjustment regulation.

A citizen wave to reclaim public and democratic water in Catalan municipalities

The year 2016 was a turning point in the management of water in Cata- lonia and throughout Spain. In March, a judgment of the Court of Justice of Catalonia cancelled the public-private partnership contract for wa- ter supply to 23 municipalities in the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona. In April, Collbató, a village of 4,000 inhabitants, became the 12th munic- ipality to recover water service management in Catalonia. Water losses in its network were more than 60 per cent. Then in November, the first meeting of Spanish cities for public water was organised in Madrid, with the participation of seven mayors from some of the largest cities in Spain, along with public water operators and civil society organisations. The ob- jective of this unprecedented event was to strengthen and coordinate the water movement across Spain, in a context where the central government is strongly opposed to remunicipalisation. Finally, in December, after 75 years of concession, the contract of private company Mina Pública de Ter- rassa (35.5 per cent owned by Agbar) with the city of Terrassa (215,000 inhabitants) was put to an end.

The trend has continued in 2017, with nine municipalities in the Metro- politan Area of Barcelona – representing three in four inhabitants – ap- proving motions in favour of considering public management of water. On 19 March 2017, Terrassa saw the first popular demonstration in favour of the public management of water in Catalonia with the participation of 4,000 people. Three days later, a Catalan Association of Municipalities for Public Management of Water was created. The municipalities involved in this new Association include Barcelona, Badalona, Cerdanyola del Valles, El Prat de Llobregat, Sabadell, Terrassa and Santa Coloma de Gramenet, representing a total of 2.5 million inhabitants. Its objective is to develop a new public model including new forms of social control to ensure trans- parency, information, accountability and effective citizen participation. The Association is committed to providing assistance, knowledge and support to those municipalities wishing to remunicipalise and implement this new management model.

This radical shift toward a new model for public water is largely the re- sult of the efforts of the many civil society platforms that organised years ago and have been denouncing irregularities and private profiteering ever since: Taula de l’Aigua (Water Table) in Terrassa; Aigua és Vida Girona (Wa- ter is Life Girona) in Girona, a city whose contract is set to expire in 2020; Aigua és Vida Anoia (Water is Life Anoia) in Igualada; Volem l’aigua Clara i Neta (We want clean and clear water) in Torello, where the contract ex- pires in 2018; Taula de l’Aigua de Mollet (Mollet Water Table) in Mollet del Vallès, where the council has already approved a study of remunicipali- sation when its contract expires in 2020; and Aigua és democràcia (Water is Democracy) in La Llagosta.

Terrassa: Ending a concession after 75 years

Private company Mina d’Aigües de Terrassa S.A. has managed the water service in Terrassa for 75 years, through a concession that ended on 9 December 2016. Since March 2014, a group of people from neighbour- hood movements, social movements and ordinary citizens created Taula de l’Aigua, a citizen platform that aims to recover direct public manage- ment of water in Terrassa, with citizen participation and social control. Mina is a subsidiary company of the Agbar Group, which controls its management and has a 35.5 per cent stake in the company. In 2013, as first evidence of a simmering conflict, it presented to the City Council a proposal to increase the price of water by 6 per cent. The Council asked for a justification and ended up rejecting the proposed tariff hike, as did the Price Commission of Catalonia, in favour of a 1.25 per cent increase. With the end of the concession approaching, the city began investigating into its options and requesting information from Mina, which it had nev- er done before. Citizens also requested information from the City Council, but Mina refused to provide most of the information. Important aspects such as the price of Mina’s water wells or the breakdown of the costs of the service are not yet public. The Mayor of Terrassa clearly expressed his dissatisfaction with the way the company, which is supposed to be a service provider for the Council, was retaining information in order to hinder a possible remunicipalisation. Two years of intensive informative and educational work done by Taula de l’Aigua succeeded in making the water issue central to the political agen- da. In July 2016, the City Council approved a motion in favour of direct management of water. Among the 27 city councillors, 20 were in favour, three abstained and four were against. The private company claimed that recovering the service would cost the city €60 million. The Council, how- ever, maintains that the cost will not be more than €2 million. When the council confirmed the end of the concession and the return of the system to the city in December 2016, Mina turned to the courts to have the reso- lutions cancelled, so far without success. The second step was to design the new public service. Taula de l’Aigua de Terrassa together with the Terrassa Council of Organisations convened the first Terrassa Citizen Parliament, which approved two motions to be presented to the City Council, on the objectives of the new management model and on social control of the service. To reclaim public and dem- ocratic water, a wide public demonstration was organised in Terrassa in March 2017 in support of the Council’s decision to end the contract.

In April 2017, the City Council of Terrassa initiated the process of devel- oping a new model for managing public water supply in the city, which must be approved before the end of 2017. In the meantime, Mina has been granted temporary contract extensions.

Terrassa demonstration

Photo by EPSU, Twitter

Over 4,000 people took to the streets to celebrate the turning tide of public water services at the World Water Day 2017 in Terrassa

Throughout this process, Taula de l’Aigua will continue promoting the management model approved by the Terrassa Citizen Parliament in February 2017, to make sure the recovery of public water in Terrassa is also a step forward in managing water as a common good.

The remunicipalisation of water in Terrassa is currently the spearhead of the recovery of public water in Catalonia, just as remunicipalisationof water is the spearhead of that of other basic services. Therefore, the success of the Terrassa remunicipalisation and the implementation of a new management model with effective citizen participation would open the door for many other progressive and democratic remunicipalisations in Catalan cities. Barcelona: A historical opportunity Next on the list could be the city of Barcelona, along with the 22 mu- nicipalities in its metropolitan area. Barcelona’s water has always been under the control of private company Agbar, with no proper contract. In 2010, a judge finally ruled this situation to be illegal, forcing Agbar and the Barcelona Metropolitan Area to sign a public-private partnership (PPP) contract in haste to regularise the situation. Initially, Agbar had 85 per cent of the PPP and the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona, 15 per cent. Subsequently, Agbar transferred 15 per cent of its shares to Spanish bank La Caixa. But this new PPP contract was approved for 35 years without a tendering process and without sufficient technical justification. For these reasons, in 2016 the Supreme Court of Catalonia cancelled the contract. Agbar has filed an appeal with the Supreme Court of Spain to override the ruling. Meanwhile, the Barcelona City Council has already approved a study for the municipalisation of the service and the preparation of technical and/ or legal reports necessary for the transition to public management of wa- ter. Eau de Paris, the remunicipalised water operator of the French capital, has agreed to provide legal and technical support for this work, while Agbar, again, refuses to co-operate and to provide information. Eight city councils from the metropolitan area have followed in the footsteps of Barcelona and have approved motions in favour of public management of water. In parallel, the city of Barcelona has already remunicipalised several public services (kindergartens and gender violence prevention) and created a new public electricity company.

Participation as an anchor

Remunicipalisation is not only a matter of municipalities recovering pub- lic management and restoring public governance. If we really want re- municipalisation to endure and lead to democratic, effective and sustain- able water services, we need to manage water as a common good. This is why citizen participation is crucial within the remunicipalised public services, just as it has been crucial in pushing for remunicipalisation in Catalonia in the first place.

Water is life not only for people, who cannot live without water, but also for the environment, which involves protecting the quality of water and ecological flows in rivers. This is especially important in Mediterrane- an regions such as Catalonia, which aresubject to the impacts of climate change. Strong citizen mobilisation for water in Catalonia has always been related to this sense of the vital importance of water as a common good. (Re)municipalisations of water are a tool to move a step forward and require municipalities to develop water policy that takes into account the limits and the quality of local water sources. Water management is a key tool for ensuring regional balance and respect for the environment, based on a concept of water not as a resource, but as a natural good, and an essential part of the ecosystem in which we live.

What form should citizen participation take? Each municipality, each platform must define what form of governance and management ensures better involvement of their citizens. What is there that already exists in the municipality’s social fabric? What spaces for participation are there? Which new ones should be opened up? Who should participate? On which decisions should citizens be engaged?

Participation must be the anchor of a new water management model. This model needs to ensure that the reclaiming of public water manage- ment in municipalities results into truly democratic deepening, through mechanisms of transparency, accountability, education and training for citizens. All this in order to keep at bay the old practices of the private management model, characterised by opacity, corruption and enrich- ment through water.

Download here for the complete Appendix: End of concession dates

*** Míriam Planas is a member of Engineering without Borders Catalonia, working for development cooperation to guarantee universal access to basic services. She is also actively involved in Aigua és Vida, the citizen platform in Catalonia, which consists of more than 50 organisations working toward public, democratic and non-commercial water management.

Informe de Fiscalización del Sector Público Local, ejercicio 2011: http://www.tcu.es/reposito- rio/fd3654bc-3504-4181-ade5-63e8a0dea5c2/I1010.pdf

See the detailed case of Valladolid on the Remunicipalisation Tracker: http://remunicipalisati- on.org/#case_Valladolid

Eldiario.es (2017) El Gobierno carga contra los procesos de remunicipalización de los Ayun- tamientos a través de los Presupuestos, 16 April. http://www.eldiario.es/politica/remunicipali- zacion-presupuestos-ayuntamientos_0_631686916.html

Eldiario.es (2017) Montoro se enfrenta a Valladolid y se persona por primera vez en una causa de remunicipalización del agua, 31 March. http://www.eldiario.es/politica/Hacienda-persona-primera-remunicipalizacion-servi- cio_0_627488367.html