State or cooperative ownership? Two means of restructuring public service in the German energy transition

March 15, 2018 | Sören Becker

Energy as a core public service

Energy systems are embedded in the social relations they enable. The way we harvest and use energy for production, recreation and transport is a vital condition of modern life, and a condition of capitalism as a regime of production and a form of society (Altvater 2007, Huber 2009). Regarding recent openings and transitions towards renewable energy, optimists here refer to Hermann Scheer’s (2007) hypothesis that the decentralised character of renewable energy technologies would also lead to more decentralised ownership structures, and hence a more democratic energy system.

I will not discuss the extent to which these expectations are fulfilled or not, I will seize the opportunity of this short paper to shed some light into the different aspects of organisation and ownership that came to the fore within Germany’s energy transition. I will contrast the cooperative model with a new form of public ownership proposed by social movements: the participatory utility. This short discussion could inform debates about how to organise alternative aims and pathways for participation in public services, in the energy sector and beyond.

New forms of ownership in the German energy transition

From 2005 onwards there are two major trends that challenge concentrated structure of energy markets: the increasing numbers of energy cooperatives and remunicipalisation, meaning the (re-)introduction of state ownership. Both of them depict collective forms of ownership that are distinct from privatised structures which were established before in the wake of liberalisation. Both were set in the context of the roll-out of renewable energy as a tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and complement to the phase-out of nuclear energy in Germany (Gailing and Röhring 2016a). Noteworthy, it was the funding scheme based on feed-in tariffs (according to the Renewable Energy Act EEG) which rendered even small-scale, “citizen energy” installations a good investment (Holstenkamp and Kahla 2016, Islar and Busch 2016); and that resulted in a largely decentralised ownership pattern for renewable energy installations. In a study for the year 2012, it was found that about 50 per cent of all renewable energy capacities in Germany are owned by either citizens or farming businesses (trend:research and Leuphana Universität Lüneburg 2013). This shift towards smaller forms of ownership has thus also been interpreted as a decentralisation of energy provision, both in organisational and spatial terms (Gailing and Röhring 2016b, Klagge and Brocke 2012). Similar developments are discussed internationally; see for example the discussion on “community energy” in the United Kingdom (Becker et al. 2017, Seyfang et al. 2013). So to speak, the transition towards renewable energy opened up a new field of energy technology that was occupied by new actors as owners and new spatial dynamics in the context of Germany’s energy transition.

Out of these different collective forms of ownership, energy cooperatives gained most attention in research and public discourse (Yildiz et al. 2016). This is due to an unprecedented dynamic in the formation of energy cooperatives. Since 2005, 812 energy cooperatives were founded with an accumulated number of about 165,000 members, producing an average of 223 members per cooperative (DGRV 2016). Out of these, 86 per cent are active in the generation of electricity, mainly through wind and solar capacities built up. These cooperatives sell renewable electricity according to the feed-in tariff scheme of the Renewable Energy Act. 19 per cent of German energy cooperatives run district heating networks that provide members with heat through mostly insulated networks. Here the cooperative does not only own the capacities for heat generation, but also the adjacent distribution grids. 1 per cent of the cooperatives is running or seeking to run an electricity grid, on a local or regional basis. These cooperatives ideal-typically do not own generation facilities. With recent changes that include the stepwise replacement of the feed-in-tariff system by an auction model prompting allocating bigger installations, the dynamic of cooperative foundation has decelerated (Müller and Holstenkamp 2015). As will be shown below, energy cooperatives are a means to directly involve citizens as owners of energy infrastructure, their political features, however, are sometimes difficult to assess.

Remunicipalisations are a slightly different, but a no less dynamic phenomenon. Remunicipalisations refer to the (re-)introduction of local state ownership in energy infrastructures and/or utilities. Remunicipalisations are an international phenomenon that covers a wide variety of sectors, including waste, water, public transport and other municipal services (Hall et al. 2013, Kishimoto and Petitjena 2017). However, the dimension of remunicipalisations in the German energy sector is without equivalent in other countries or sectors (ibid.). Counting new entries in commercial registers, Lormes (2016) accounted for 122 newly founded local utilities from 2005 to mid-2014 (p. 334). These make up a large part of the 845 local utilities accounted in the official statistics of the year 2011 (ibid.). 90 per cent of these occurred in municipalities with less than 50,000 inhabitants, two third even in the range of municipalities with 10,001 to 20,000 inhabitants. These numbers also include intercommunal cooperation which are more likely to occur in smaller communities (ibid: 334). Other studies relying on different methods of data gathering, including studies of press reports or surveys among trade union members or data provided by the Association of Municipal Enterprises (VKU), confirm these numbers and the information on their spatial distribution and size of the municipalities that remunicipalised at least parts of their system (Berlo and Wagner 2013). While motivations for remunicipalisations span a wide range of arguments including local benefits, employment, and restoring local control over the direction and quality of energy provision, some instances were also based on prospects for accelerating a local energy transition.

New forms of organising participatory public services

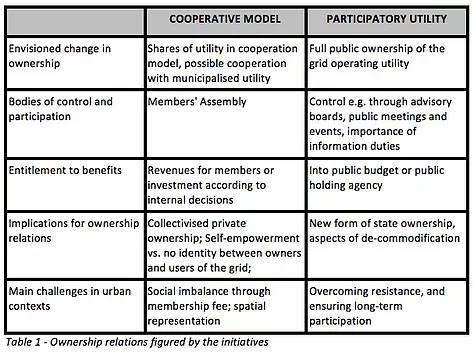

This section discusses the concepts according to which four initiatives (one remunicipalisation initiative and one energy cooperative in the cities of Hamburg and Berlin) wanted to restructure ownership relations in the energy provision. It lays out which visions and imaginaries have guided their concepts, but also which are the challenges implied in each of these. These ideas are important in two ways: first, they spell out different forms of participation that contest the given structures around private ownership entitlements. Second, these visions develop forms and strategies to democratise state institutions in a way that would open these up to social movement and citizen demands for equal and sustainable public service provision. As carved out in their publications, however, the pathways for reframing this relationship differ according to the models of ownership: BürgerEnergie Berlin and Energienetz Hamburg are cooperatives relying on membership, while the two remunicipalisation initiatives figure utility ownership by the local state which should be complemented by participatory provisions. This implies a public utility of a new kind; therefore I speak of a “participatory utility”.

To compare their visions, five criteria were derived from the conceptualisation of ownership as entitlement for control and benefits. These encompass: a) the envisioned change in ownership, in other words, the ownership model the initiatives have targeted; b) the bodies of control and participation envisioned; c) the entitlements for benefits; d) the implications for ownership relations; and e) the main challenges of each model for the implementation of its principles in a diverse urban context (see Table 5).

The cooperatives wanted to achieve a situation in which they would own a part of the shares of the grid operating utility, according to the amount of capital gathered through membership fees and donations. The impetus behind that was to secure citizen influence as a minority shareholder with special rights negotiated with the other owner parties. Thereby the cooperative concept does not necessarily entail a new role for the state in energy provision, although cooperative members stated in interviews that they would rather join forces with a public than a private utility.

The cooperative model defines ownership relations around the principle of membership. That means that the Members’ Assembly is the most important body of control. Here, the fundamental decisions on the strategy of the cooperative are made, while each member therein has one vote regardless of the number of shares owned (Schröder and Walk 2014). Also, members are entitled to share the benefits of operations, or to decide what they should be used for. To become a member, a membership fee is necessary (100€ for Energy Network Hamburg; 5 x 100€ for Citizen Energy Berlin). While others have highlighted that energy cooperatives can be interpreted as self-empowerment for people to their energy system (van der Schoor and Scholtens 2015), it is important to note that there is no identity between owners and users in this model (cf. Novy 1985: 127). In an abstract sense one can argue that the entitlements implied in the ownership relation as such are transferred to the collective of the members; which, in turn, is still constituted of a limited group of owners. In this sense, the cooperative model could be described as “collectivised private ownership”. The two main challenges deriving from this ownership model refer to, first, the unknown extent of rights granted to the cooperative for having an effective influence on the business strategy of the grid operator they own minority shares; and, second, a potential social and spatial imbalance as the fee granting admission could become a hurdle for poorer households to become a member. The latter could also have a spatial implication on membership when there is a higher representation of more affluent neighbourhoods within the city itself. In order to gain as much capital as possible, none of the cooperatives has been restricted to citizens of the respective cities only, so that also interested non-locals could become members (yet there is no spatial data on the ownership structure available). Summing up, the cooperative model provides for a high degree of internal equality and democracy, while their general scope is, at the same time, limited by the membership approach and the necessary cooperation with another utility.

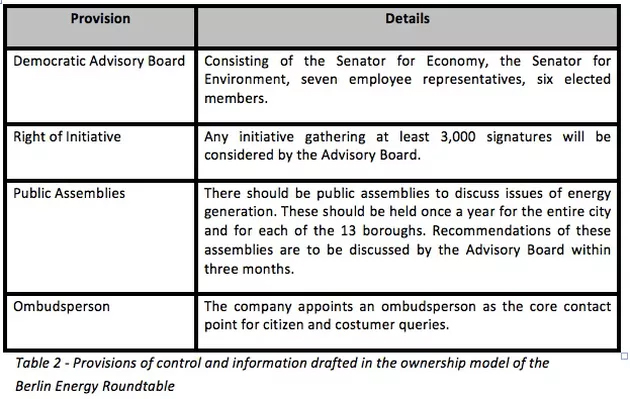

Against the internally democratic, but limited approach of the cooperative model, the approach of the participatory utility is wider in scope. The initiatives here targeted full public ownership of the physical grid and the operating utility. In this sense, the control and entitlements to benefits produced by grid operation should be transferred to the state. Noteworthy, what the initiatives had in mind was more than a traditional local public utility; instead they were striving for public ownership tied to targets around renewable energy and social equity, and, most important here, citizen participation and control. For this reason, remunicipalisation initiatives in both cities either have inscribed the principle of democracy (as in Hamburg) or deliberately spelled out concrete participatory and information mechanisms (as in Berlin) into the voting template for the referendum. Table 6 here shows the different provisions for control and information considered in the Berlin model in an exemplary way. The intention is to enable citizens to exert influence on the guidelines and practices of the utility. This should be achieved through designing organisations that have inscribed information and participation duties. Hence, the entitlements of control here differ from traditional models of public ownership with more limited means of control. These provisions, taken together, put forward a new form of state ownership enriched by models of participation and steps towards de-commodification, in the sense of both user integration and non-financial aims.

This participatory approach is meant to ensure the ambitions of the project itself. Past evidence shows that public ownership does neither prevent a commercialisation, nor a future privatisation of the utilities (Wissen and Naumann 2006). Hence the activists were sceptical towards the state as the embodiment of general interest of its population. The solution here was to institutionally design a utility that would be open for citizen, and, hence, social movement demands even in the long term. Further, the more “soft” aims of social justice and climate compatibility should also be inscribed into the practice of the utilities. However, therein lay two main challenges: first, the ongoing discussions about the referendum in Hamburg show that in the phase of implementation there are a number of resistances to be overcome, for example referring to different notions of how to actually fulfil the aim of social justice or democracy in the design and practice of the utility, potentially diluting the original aims of the initiatives. Even if participatory provisions as means for user and social movement influence are actualised, the second challenge here rests in ensuring their effective use over the long term. Overall, the participatory utility approach in both cities extends traditional ownership relations as they spell out and redefine entitlements for control, and potentially also for the use of benefits.

A short conclusion

Summing up, both remunicipalisation initiatives and energy cooperatives have outlined alternative forms of ownership for the energy provision of the two cities, each according to their own organisational model. If actualised they would redefine the relations of ownership in energy, in the sense of reversing privatisations in the two cities, and in a more underlying sense of redefining who controls and benefits from the operation of the energy network. In the cooperative model, the group of owners would be widened to those who became members of the cooperative, in the participatory utility citizens would be granted rights of information and participation. In a broader picture, these suggestions carry the potential to also redefine the relations between the state, private businesses and citizens in energy provision – in the way of inscribing entitlements of control for mainly citizens, while also ascribing a core role to the state. In short, while the biggest challenge in the cooperative model is ensure an egalitarian representation of the population as cooperative members, the crucial point in the participatory state model is to actually realise effective participation of everyone interested. The implementation of such models, of course, relies on the power geometries that define political struggles. Interestingly, it happened in the crucial sector of energy that these openings could be seized, yet, a transfer of these models and the debate around it to other sectors of public services need to take into account their specific conditions, technological and organisational arrangements, and lastly, their regulatory framing.

REFERENCES

Altvater, Elmar (2007): The social and natural environment of fossil capitalism. In: 43, pp. 37–59.

Becker, Sören; Kunze, Conrad; Vancea, Mihaela (2017): Community energy and social entrepreneurship: addressing purpose, organisation and embeddedness of renewable energy projects. In: Journal of Cleaner Production 147, pp. 25–36. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.048.

Berlo, Kurt; Wagner, Oliver (2013): Stadtwerkeneugründungen und Rekommunalisierungen. Energieversorgung in kommunaler Verantwortung. Wuppertal: Wuppertal Institute. Online https://wupperinst.org/uploads/tx_wupperinst/Stadtwerke_Sondierungsstudie.pdf.

Bontrup, Heinz-J.; Marquardt, Ralf-M. (2011): . 2nd edit. Berlin: Ed. Sigma.

Gailing, Ludger; Röhring, Andreas (2016a): Is it all about collaborative governance? Alternative ways of understanding the success of energy regions. In: –10.1016/j.jup.2016.02.009.

Gailing, Ludger; Röhring, Andreas (2016b): Germany’s Energiewende and the spatial reconfiguration of an energy system. In: Gailing, Ludger; Moss, Timothy (eds.): . London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 11–20.

Holstenkamp, Lars; Kahla, Franziska (2016): What are community energy companies trying to accomplish? An empirical investigation of investment motives in the German case. In: 97, pp. 112–122. DOI: 10.1016/j.enpol.2016.07.010.

Huber, Matthew T. (2009): Energizing historical materialism: fossil fuels, space and the capitalist mode of production. In: 40 (1), pp. 105–115. DOI: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.08.004.

Islar, Mine; Busch, Henner (2016): “We are not in this to save the polar bears!” The link between community renewable energy development and ecological citizenship. In: 29 (3), pp. 303–319. DOI: 10.1080/13511610.2016.1188684.

Kishimoto, Satoko; Petitjean, Olivier (eds.) (2017): . Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

Klagge, Britta; Brocke, Tobias (2012): Decentralized electricity generation from renewable sources as a chance for local economic development: a qualitative study of two pioneer regions in Germany. In: 2 (1), pp. 5. DOI: 10.1186/2192-0567-2-5.

Lormes, Ivo (2016): . Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Morris, Craig; Jungjohann, Arne (2016): . Cheltenham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Müller, Jakob R.; Holstenkamp, Lars (2015): Zum Stand von Energiegenossenschaften. Aktualisierter Überblick über Zahlen und Entwicklungen. Lüneburg: Leuphana Universität Lüneburg. Online http://www.leuphana.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Forschungseinrichtungen/professuren/finanzierung-finanzwirtschaft/files/Arbeitspapiere/wpbl20_energiegenossenschaften2014_final.pdf.

Novy, Klaus (1985): Vorwärts immer – rückwärts nimmer: historische Anmerkungen zu einem aktuellen Problem. In: Bierbaum, Heinz; Riege, Marlo (eds.): . Hamburg: VSA, pp. 124-141.

Scheer, Hermann (2007): . London; Sterling: Earthscan.

Schröder, Katrin; Walk, Heike (2014): Opportunities and limits of cooperatives in times of socio-ecological transformation. In: Freise, Matthias; Hallmann, Thorsten (Eds.), Modernising Democracy? Associations and Associating in the 21st Century. Springer, New York, pp. 301-314

Seyfang, Gill; Park, Jung Jin; Smith, Adrian (2013): A thousand flowers blooming? An examination of community energy in the UK. In: 61, pp. 977–989. DOI: 10.1016/j.enpol.2013.06.030.

trend:research; Leuphana Universität Lüneburg (2013): . Bremen, Lüneburg. Online https://www.buendnis-buergerenergie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/Studien/Studie_Definition_und_Marktanalyse_von_Buergerenergie_in_Deutschland_BBEn.pdf.

van der Schoor, Tineke; Scholtens, Bert (2015): Power to the people: local community initiatives and the transition to sustainable energy. In: 43, pp. 666–675. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2014.10.089.

Wissen, Markus; Naumann, Matthias (2006): A new logic of infrastructure supply: the commercialisation of water and the transformation of urban governance in Germany. In: 33 (3), pp. 20–37.

Yildiz, Özgür; Rommel, Jens; Debor, Sarah; Holstenkamp, Lars; Mey, Franziska; Müller, Jakob R. et al. (2015): Renewable energy cooperatives as gatekeepers or facilitators? Recent developments in Germany and a multidisciplinary research agenda. In: Energy Research & Social Science 6, pp. 59–73. DOI: 10.1016/j.erss.2014.12.001.

* Dr. Sören Becker is a geographer interested in alternative ways of organizing infrastructure and technology in cities. He works and publishes on energy remunicipalisation and community energy was published in various academic articles. He is working as a researcher at the University of Bonn and Humboldt University Berlin.