Southeast Asia: Social Protection rhetoric versus exclusionary socio-economic policies

Notes prepared for the International Conference on Universal Social Protection and Labor, organized by the Asia-Europe People’s Forum and Nepal Partners. Held at Kathmandu, Nepal, April 4-6, 2019.

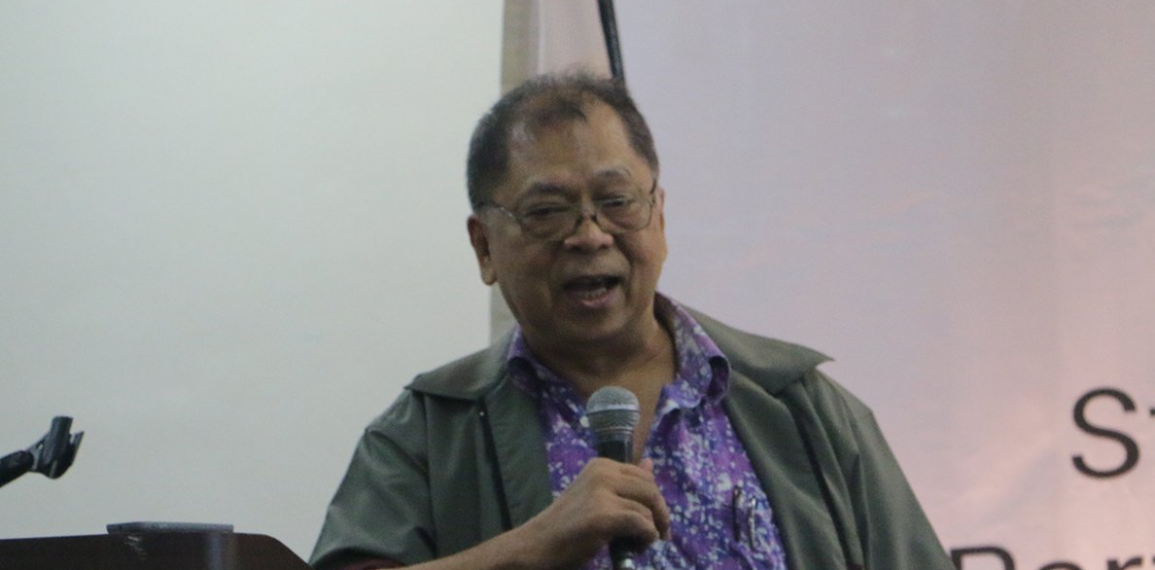

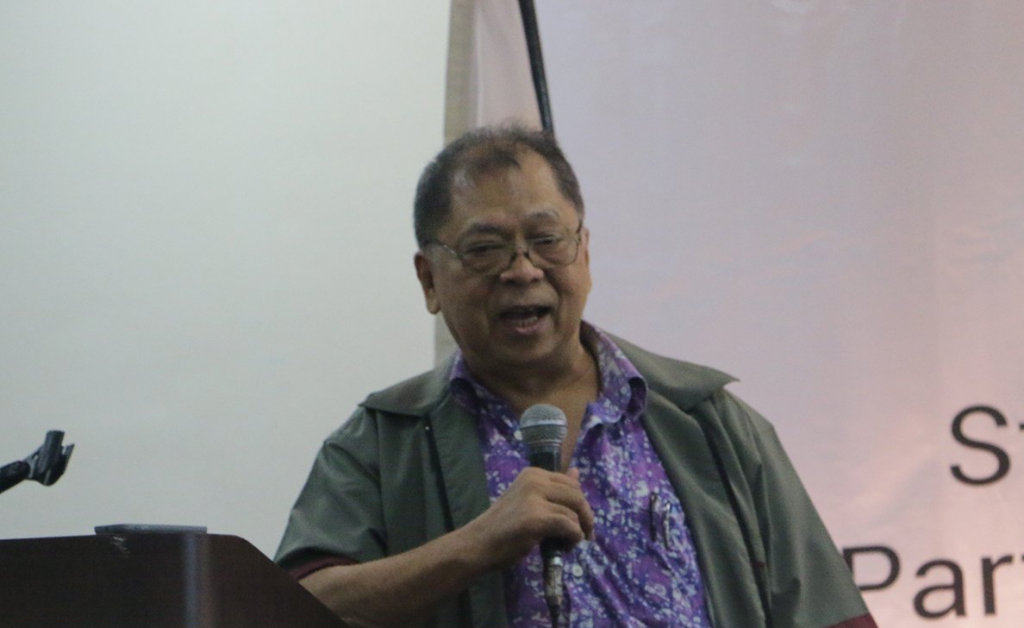

Rene E. Ofreneo

(President, Freedom from Debt Coalition, Philippines)

- Two decades ago (1997-98), Southeast Asia gave the world the “tom-yung” financial crisis, better known as the Asian financial crisis (AFC). Four Asian countries sunk into depression: Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea and Thailand. The Philippines and other Asian countries, including Russia and some countries in Latin American countries were shaken. The AFC was followed a decade after (2007-2010) by the bigger global financial crisis (GFC), which originated from the heartland of financial capitalism: New York and London.

- Millions lost jobs overnight in Southeast Asia due to the AFC. Indonesian strongman Suharto himself lost his job, after meekly submitting his country to the supervision of the IMF.

- It was against this backdrop that some serious re-thinking about social protection took place within the official policy circles in Southeast Asia. In the 1980s-1990s, the World Bank and its neo-liberal cohorts actively promoted the privatization of government-managed pension and social security programs, as part of the broader program of privatizing, deregulating and liberalizing economies of the world. This privatization proposal was meaningless to all those who lost their jobs and incomes due to the AFC.

- In Thailand, the government of the populist Thaksin Shinawatra pushed for the 40-baht universal health care despite the earlier austerity program pushed by the IMF-World Bank group. In Malaysia, Mahathir defied the IMF by imposing capital controls to stop the haemorrhage of capital and jobs out of the country. But the beleaguered Suharto completely succumbed to the IMF diktat.

- And yet, ten years after, at the height of the GFC, the world re-discovered the Keynesian approach in crisis situations, that is, government stimulating the economy through various deficit spending mechanisms. In America, the spending program was even seized by the big banks, which precipitated the crisis, as a means to save themselves by arguing that their collapse will lead to the bigger collapse of the economy. These banks that were projected as “too big to fail”. In 2017, the IMF Research Department wrote a “mea culpa” on capital controls, virtually telling the world that Mahathir, the medical doctor, was correct in making interventions in the capital market in 1997-98.

- The foregoing narrative on IMF-World Bank policy with somersaults on austerity and capital controls shows that there are social and economic realities on the ground that cannot be ignored. These realities are forcing these institutions to adjust their neo-liberal lenses somewhat somehow.

- One important adjustment is the way these lenders and their neo-liberal supporters are treating social protection. In the 1980s-1990s, the ILO had a weak program on social protection. But from the turn of the millennium, the ILO has become more assertive. In 2012, the ILO’s concept of the social protection floor has gained global acceptance with the adoption of Resolution 202.

- This ILO Resolution is now supported by the World Bank, which has been collaborating with the ILO in a number of social protection promotion programs. The World Bank also stopped talking of pension privatization, after strong criticisms by Joseph Stiglitz. One major program of the World Bank is the promotion in Asia of its Latin American experiment called “Bolsa de Familia” or conditional cash transfer (CCT). Under the CCT, minimal monthly allowance is given to poor mothers on the condition that the mothers get maternal medical check-up and her school-age children continue to go to the schools.

- In Southeast Asia in the meantime, the Thaksin universal health care initiative has also gained wider acceptance in some countries, in Indonesia and the Philippines in particular. Social protection has also become a major ASEAN theme since 2007, when the ASEAN Charter was adopted. Thus, there has been a proliferation of social protection programs being bandied around or being proposed, with the World Bank and ADB coming in now as the social protection champions and supporters. In 2013, the ASEAN came up with a sweeping Declaration on Strengthening Social Protection, which cites all UN conventions on economic and social rights that citizens should be able to get. There are other ASEAN Declarations: an ASEAN Declaration on Ageing: Empowering Older Persons in ASEAN, an ASEAN Declaration on Strengthening Family Institutions, an ASEAN Declaration on the Enhancement of the Role and Participation of Persons with Disabilities, and an ASEAN Declaration on the Enhancement of the Welfare and Development of ASEAN Women and Children. Today, the ASEAN has been organizing numerous ministerial meetings on how to push social protection through the ASEAN Strategic Framework on Social Welfare and Development (2016-2020).

- At the level of the individual ASEAN countries, political leaders also talk endlessly on the need for social protection — universal health care, education, pension for the retirees, social assistance to the disabled, etc. – for the poor and those in the margin of society. The only limit is budget that can be allotted for this purpose, or money that can be borrowed from the World Bank, ADB and other aid givers, again for this purpose.

- And this is precisely the problem. The issue of social protection, now accepted and articulated by government officials, has become a question of budgetary allocation. The deeper problem on why there are so many poor and so many are on the margins is not being addressed fully. More importantly, neo-liberal policies that are in place and the neo-liberal thinking that still dominates general economic policy formulation are not being questioned. For example, the privatization of public services such as water and electricity, instead of being kept in the hands of government to ensure universal access for all, is still a priority program in many countries. These are usually bundled under what the technocrats call as the Public-Private Partnership (PPP), a scheme pioneered in London under Margaret Thatcher. Under the PPPs or their hybrid forms in Southeast Asia, the big private service providers are able to transform natural monopolies into private sector monopolies. As a result, inequality is deepening and the exclusion of the many is being exacerbated.

- Worse, programs or policies that are anti-poor deepen poverty and the lack of social protection for them. Example: many peasants, indigenous people and rural poor are being displaced due to the rapacious land accumulation programs of the big land developers, the big agribusiness investors and the members of the national elite who want to get the best lands. In this process, the displaced become the “floating population” of poor circulating within countries. They join the huge army of the ‘informals’ who constitute two-thirds of the labor force in most countries. They include the home-based workers, the street vendors, the informal transport workers/operators and the coastal fisherfolks. Most of the informal labour do not get adequate social protection, only paltry social assistance programs that are dependent on limited budgetary allocations of governments.

- In the formal labor market, there are also problems. The army of the precariat continues to grow, partly because of the efforts of neo-liberal economists and corporations to pressure governments to maintain labor flexibility policy, meaning employers can hire or fire workers at will. The non-standard or non-regular paid workers, who outnumber the regulars, are often not given formal employment contracts nor are they enrolled by their employers in the social security system.

- To complete the labor market picture, the floating population of displaced landless rural poor and jobless urban poor is supplemented by the floating population of migrant workers crossing borders. There are varied estimates on their number. In Southeast Asia, the biggest destination countries are Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand. A number of migrants are doing well. But majority, who occupy the low-end jobs are shunned by the nationals of the destination countries, and are in the most vulnerable position, with limited access to legal and social protection assistance. Again, increased migration is largely the outcome of poor economic policies at home, while those using migrants’ services are able to restrain wage increases in their own countries.

- So how then do we wipe out poverty and provide social protection for all given the foregoing?

- In the ASEAN, the good thing is the rising awareness within policy circles on the importance of providing universal social protection, starting with universal health care. The sad part is: all this is treated as a funding or budgetary issue. There are numerous meetings and workshops on social protection or various aspects of social protection such as systems of delivering services, packaging the services and so on. But rarely is there an exhaustive and serious discussion on the root causes of poverty and social exclusion.

- And yet, the reality is that universal and adequate social protection is not possible if there are no meaningful social and economic reforms to ensure that economic growth is inclusive, balanced and sustainable. The point is that a program of social protection should be part of a bigger transformation program. It means discarding the neo-liberal assumption that growth automatically trickles down to the benefit of the poor. There is a need for re-thinkinging and transformation too of the overall design of regional and global integration. Why should countries at different levels of development be subjected to uniform rules for the rich and poor countries? Each country, given the level of its development, should be given the freedom to determine its development priorities based on the principle of special and differential treatment. As well as needs of their people.

- Socio-economic transformation programs should be synchronized too with programs dealing with transitions – just transition in addressing problems of the environment and climate change risks and just transition to prepare the people on the impact of rapid technological change under the ongoing Fourth Industrial Revolution. On the environment, climate change risks are mounting everywhere and decimating agriculture, water systems and so on.

- On the other hand, the technology revolution is subverting Factory Asia, which is based on international subcontracting initiated by the multinationals in the car, electronics and so many industries. Some institutions, including ironically the ILO, are talking of scaling up developing countries’ participation in the global value chains when the reality is that these GVCs are now being reconfigured because of robotization and automation. Also, there is no way, the laggards can graduate to a higher level of development if they simply tie their fate to the coattails of the GVCs of the MNCs.

- So, it is an urgent task for governments and the working peoples to come up with just transition programs tailored and sustainable within the parameters of the environment and the technology revolution. ‘Just’ here means just transformation programs involving the people every step of the way. For example, cleaning a coastal area should not lead to the displacement of the coastal fishing community but should enable the community to become partners and keepers of clean coastal areas while building a prosperous fishing community.

- Clearly, so much has to be done. The task of securing universal, adequate and comprehensive social protection for all cannot be reduced to a mere question of creating the fiscal space for this such as generating new taxes. The most basic is how to align social and economic policies in support of inclusion and sustainability by abandoning the neo-liberal development straitjacket and by abandoning the regional and global Race to the Bottom in the treatment of workers and resources of a country. We need to embrace a new paradigm of regional and global integration, where people are truly at the center of development.