China and the World: An introduction for activists

By Sophie Chen

Introduction to the ‘China and the World’ series

China, the world’s second largest economy, ranks first in outward foreign direct investment (FDI), and is the global leader in artificial intelligence (AI) and renewable energies. Global capitalism would not survive in its current form without China’s dynamism and pivotal role. Worldwide people are connected to China – as consumers, contractors, business partners and borrowers. With its increased economic and political power, the Chinese state is playing an increasingly assertive global role, looking to consolidate power at home and abroad. These relationships affect people within China and worldwide.

There is considerable academic and media discussion about China’s international ascent, but the phenomenon is often portrayed inaccurately, with no reference to China’s unique history, political institutions, or the accounts of its population. China is not just its state or government, but also its people. Yet extensive domestic censorship and lack of freely accessible information make it difficult to develop an updated and accurate analysis. As China’s global impact grows, it becomes increasingly important to deepen international understanding of China, to amplify voices from grassroots social movements inside the country and, more importantly, to show solidarity and learn from their experiences and resistance.

To challenge some of the common myths, and offer a more contextualised perspective, Transnational Institute, gongchao.org, Made In China Journal, Lausan, Critical China Scholars, Positions Politics and the Asia-Europe Peoples’ Forum co-organised a webinar series covering six major topics ranging from China’s political and economic system to its global impact. The webinars brought together activists and scholars. This briefing is based on the insights shared during the webinars. Links to source material are embedded throughout the briefing, and relevant resources are listed at the end of each section.

Resources

- Franceschini, I., Loubere, N. and Sorace, C. (eds.) (2019) The Afterlives of Chinese Communism: Political Concepts from Mao to Xi. ANU Press & Verso.

- Karl, R. (2020) China’s Revolutions in the Modern World: A Brief Interpretive History. New York: Verso.

- Made in China journals: https://madeinchinajournal.com/

- Positions Politics website: https://positionspolitics.org/

- Spence, J. (1999) The Search for Modern China. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Wasserstrom, J.N. (2022) The Oxford History of Modern China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Life In China

Over the last 30 years, China has undergone dramatic economic growth and social transformation, bringing enormous changes in the daily lives of ordinary people. Often overlooked in the Chinese government’s grand narrative and its large-scale social engineering projects, however, are the lives of women, workers, and ethnic minorities in the country’s changing political and economic structure.

Women in China

After the Communist Party took power in 1949, the Chinese state introduced a series of laws to narrow gender gaps. In 1950, the first Marriage Law was passed to prohibit arranged marriage and child betrothal, which had existed since the imperial era. The new constitution stated that women enjoy equal rights with men in all aspects of political, economic, cultural, social, and family life.

In the state socialist era (1949–1976), ‘women can hold up half the sky’ was a symbolic and widely used slogan. As the state pushed industrial accumulation and agricultural production, women were mobilised to work in factories or agriculture. To support women’s full employment, the government promised to socialise much of women’s domestic work. As a result, women’s labour participation rate reached nearly 90%, among the highest worldwide. Despite this, the gendered division of labour in the household and public sphere remained intact. Women still had to bear most of the burden for unwaged reproduction work. New gendered divisions also emerged in the productive sector. In most workplaces, male workers were concentrated in the skilled positions in heavy industries, whereas female workers were concentrated in low-end positions in service and light industries.

In the wake of the economic reform, which began in 1978, women in China have faced widening gender gaps in both their participation in the labour force and in wages. By 2000, most government-run childcare facilities were privatised or shut down, which moved the parenting burden to working women and jeopardised their position in the labour market. In contrast to the mobilisation of women’s labour in the socialist era, from the 1980s some male intellectuals began calling for women to ‘go back home’ to fulfil their domestic duties. Women have also faced increasing pressure to enter into marriage. Between 1990 and 2018, the female labour participation rate dropped drastically from 90% to around 60%, and women’s earnings declined from about 84% of men’s wages in 2000 to 65% in 2013.

Since the early 2010s, the crisis of social reproduction has intensified. With a rapidly growing urban population and inadequate public services, the cost of social reproduction has been driven up further, which has in turn contributed to declining fertility rates. Chinese women continue to face systemic exploitation and appropriation of their reproductive labour and discrimination in the job market, although of course their experiences vary according to their social position. Women who work in the formal economy not only experience sexual harassment and earn lower wages than men, but also disproportionally shoulder the burden of childcare in the deepening class gap in the cities. Meanwhile, poor rural women have been pushed to enter informal, precarious, and poorly paid job markets to provide essential urban services. Owing to the lack of access to social welfare in the cities where they work, they are often separated from their children. These female migrant workers in China make up the world’s largest domestic service market, made up of approximately 35 million people.

In the face of this discrimination and oppression, women have not stayed silent. Chinese feminism dates from the turn of the twentieth century, when revolutionaries advocated for women’s rights as a part of national modernising project. As stated above, after the Communist Party took power, the state played a key role in launching campaigns to promote women’s legal and economic rights. More recently, between the 1990s and the early 2010s, non-government organisations (NGOs) emerged, focused on combatting domestic violence and promoting reproductive health rights. This included the ‘Anti-Domestic Violence Network’, which was shut down right before the government passed the ‘Anti-Domestic Violence Law’, for which the network had long advocated.

Over the past decade, explosive online discussions have contributed to unprecedented debate on gender issues, with wide scope and high visibility. Scholars Wu and Dong identify two major styles of expression women used during this period in a ‘Made-in-China’ feminism. The first and most pronounced is the ‘entrepreneurial’ voice, which resonates with women’s anxiety about economic security and encourages women to abandon traditional wifely duties and exercise their autonomy in deciding on marriage to maximise their personal returns. They also identify a more radical style, most represented in the ‘Young Feminist Activism’ (YFA). Since the early 2010s, this network of young students and activists has organised street demonstrations and online campaigns to against discrimination and gender-based violence and advocate for women’s rights. After the crackdown on the YFA, the #MeToo Movement, which emerged at a larger scale in 2018, has become one of the most energetic forms of activism in China today and the most pronounced critiques of the status quo. The #MeToo movement is reviewed in more detail in the later section ‘Social Movements in China’.

Workers and migration in China

At the turn of the millennium, the working class in China could be divided into two main groups: permanent workers in the old state-owned enterprise (SOE) sector and internal migrant workers originally from rural areas and working as contract workers in cities.

In the state socialist era, SOE workers held permanent jobs in public employment, and enjoyed socialist benefits from cradle to grave, such as housing and childcare benefits – all of which were distributed through membership in a work unit. However, as China accelerated its integration into the global capitalist system in the late 1990s, around 30 million SOE workers were laid off during corporate restructuring. This marked the demise of the old SOE working class, as China’s SOEs were pushed to operate as profit-driven corporations. More detail about the development of China’s economic system is reviewed in the section ‘China’s Economic System’.

China’s economic transition also increased its reliance on internal migrant workers. In the late 1970s, special economic zones (SEZs) were set up to attract foreign capital for export processing. By the 1990s, as China further opened up and became the world’s factory, tens of millions of migrant workers moved from poor rural areas to coastal cities to make a living in the hyper-exploitative manufacturing sectors producing goods for markets overseas. Transnational capital boosted its profitability through the massive relocation of global supply chains to China, where the overall enforcement of labour law was poor and basic labour rights of migrant workers were systematically abused. Migrants often worked in on-site dormitories, subjected to extremely long working hours for a meagre salary, where they suffer frequent work injuries. Moreover, workers’ right to strike was removed from the constitution in 1982, and workers’ bottom-up struggles were often repressed. The All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), the only legal trade union, is also controlled by the Party and, despite occasional bids for greater autonomy since the 1949 revolution, primarily ‘maintains stability’ and ensures that production continues, rather than representing workers’ interests. At the enterprise level, union officials are often part of the management.

The collaboration between the Chinese government and transnational capital was essential to China’s emergence as the ‘world factory’. The government identified the large rural surplus population as its ‘comparative advantage’ in the global supply chain and crafted political and social policies to facilitate massive economic growth. The hukou system, which links the provision of social services to household registration in a particular location, has served as an overall development strategy to enable cities to enjoy a cheap workforce without having to pay any of its reproduction costs. Under the hukou system, rural migrant workers are denied access to all kinds of state-subsidised social services in the cities, including health care and their children’s education. As a result, despite some variations between successive waves of migration since the late 1970s, the pattern for many migrant workers is that they work in the cities when they are young, briefly moving back to the countryside to get married and have children, and then leaving them to return to work in the cities. By 2013, 61 million children were separated from one or both of their parents. Some of these children have been subjected to sexual and physical abuse.

By 2021, there were 292 million migrant workers in China, comprising more than a third of the entire working population. In 2018, for the first time, the number of migrant workers employed in the service sector exceeded those in the manufacturing and building sectors and this share has continued to grow. Migrant workers in the cleaning, hospitality, food and logistic sectors have been crucial to sustaining the lives of the modern urban population, yet their jobs are both precarious and exploitative. In recent years, the central government has begun to address the situation of migrant workers in its rhetoric, and enacted some reforms of the hukou system. However, since the central government leaves implementation to local governments, but without providing additional resources, the welfare system remains effectively unreformed. Although restrictions on securing residence in smaller cities have been loosened, social services are still typically available only to a small number of better-educated non-locals. Registration in bigger cities, where better job opportunities are concentrated, remains extremely difficult.

In response to the exploitation and exclusion of migrant workers, there have been persistent protests and wildcat strikes. These have articulated a range of demands – from wage increases and pensions to compensation for factory relocation – and led to both repression and policy reforms. We review labour movement in China in the section ‘Social Movements in China’.

Ethnic Minorities

China’s official position is that it is a unitary multi-ethnic state comprising 56 different groups. The Han constitute a 91% absolute majority of the total population, and other ethnicities are often referred as ‘ethnic minorities’. In 1950s, the Communist Party started its ‘Ethnic Classification Project’ to call for applications from ethnic groups for official recognition. The government sent hundreds of researchers to investigate groups for classification and identification, and eventually over 400 self-reported groups were classified into 55 officially recognised minorities that could claim minority rights enshrined in the law. It is worth noting that, within the process, the government categorised the ethnic groups in a way that fit its political concerns of territorial integrity and stability. For example, the Baima and Ersu people, who are classified as Tibetans, have petitioned to be recognised as separate ethnicities, which the authorities have rejected.

As China instituted its economic reforms, the government has presented itself as an inclusive and multicultural state and invested in infrastructure in order to promote tourism. This commodified and exoticised ethnic cultural representation for domestic and international tourist markets. For instance, the provincial governor of Yunnan initiated tourism projects in Lijiang and used The Old Town, which features the Dongba culture of Naxi, to apply for the UNESCO-monitored legacy project. Meanwhile, as the central government encourages further urbanisation, some ethnic minorities in the border regions have been dispossessed from their lands and become part of the urban workforce. In the film project ‘Caches From The Landscape’, the Nomadic Department of the Interior (NDOI) features villagers in the southwestern province of Guizhou who were being displaced by the world’s largest radio telescope. It captures changes in the landscape, peoples’ collective identity, and the constant migration experienced by many ethnic minorities in China.

According to scholars Gerald Roche and James Leibold, a ‘second-generation’ of Ethnic Policies was first proposed in 2011, and has been implemented across the country since 2013. This new approach, with its more forthright embrace of cultural assimilation, marks a break from the somewhat Soviet-inspired approach adopted in earlier periods, which featured language protections and occasional rebukes of ‘great Han chauvinism’ at the same time as even while it also repressed ethnic groups, such as Tibetan and Uyghur movements. In recent years, the government has placed increasing emphasis on ‘inter-ethnic mingling’ and proactive forging of a common identity, while also promoting universalisation of Mandarin-medium education, and scaling back a range of preferential policies. The response to these policies builds on long-standing grievances and campaigns for national self-determination by groups on China’s periphery, resulting in intensified grievances and social unrest in Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and other autonomous regions. In 2020, a newly implemented language policy sparked petitions, street demonstrations, and school boycotts in Inner Mongolia autonomous region. The Chinese government has constructed a digital enclosure and mass internment system in the Uyghur autonomous region, which has detained at least one million ethnic Uighurs ( more context and details is reviewed in the later section ‘Political System’).

Webinar participants

- Yige Dong, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Gender Studies at the State University of New York, Buffalo and author of the forthcoming The Fabric of Care: Women’s Work and the Politics of Livelihood in A Chinese Mill Town.

- Eli Friedman, Associate Professor and Chair of International & Comparative Labor at Cornell University’s ILR School.

- Yutong Lin, Nomadic Department of the Interior art research collective

Resources

- Byler, D. (2021) Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Chan, J. Selden, M. and Ngai, P. (2020) Dying for an iPhone. Chicago: Haymarket.

- Friedman, E. (2022) The Urbanization of People: The Politics of Development, Labor Markets, and Schooling in the Chinese City. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Rozelle, S. and Hell, N. (2020) Invisible China. How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wang, Z. (2017) Finding Women in the State: A Socialist Feminist Revolution in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-1964. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

China’s Political System

China’s political system is often difficult for outsiders to understand. While it is often portrayed as a monolithic, top-down bureaucracy, the Chinese government claims to practise ‘whole-process people’s democracy’, a model of socialist democracy which it characterises as ‘true democracy that works’. To explore the complexity of China’s political system in its own context, it is useful to look at the dynamics from several angles, such as the class character of the Chinese state, the ways the system shapes daily life, as well as recent political events such as the government’s ‘People’s War on Terrorism’ in Xinjiang, the crackdown on Hong Kong and the response to the pandemic.

Class character of Chinese state

At the founding of People’s Republic of China in 1949, Mao proclaimed that the new socialist state would constitute a people’s democratic dictatorship, serving the class interests of the revolutionary peasant–proletarian alliance which had ushered the new state into existence. Throughout the socialist era, the state insisted on making its class character apparent and ensured the supremacy of the peasant–proletariat alliance in state practice and ideology. In other words, the state made no pretence of class neutrality, announcing that the state served the peasant–proletarian alliance and acted on behalf of the revolutionary people of China. This provided the state with its ideological legitimacy. While the state was to be democratic for those people who supported the revolutionary party and its allies, it was to prove a dictatorship to those who were considered anti-revolutionary or whose class background was suspect.

By contrast, although the state still claims universal continuity between its interests and those of the supposedly classless nation, it usually serves the interests of the wealthy and subordinates the interests of workers and peasants. During and after China’s reform era, far from retreating from social life the state has embedded itself further, issuing policies that advance the commodification of land and labour. At the same time, capitalist activity is subject to state control and surveillance. Today, although China acts in the name of socialism, the state largely serves to safeguard the conditions for capitalist accumulation and its power lies in its demonstrated capacity to ensure economic growth and stability.

The structure of China’s political system

The territories of China, especially the peripheral regions where non-Han Chinese reside, are largely a legacy of the Qing empire’s military conquest, and were inherited by the Nationalist-led Republic of China and subsequently reshaped by the upheavals of the twentieth century. Since 1949, the entire territory has been ruled by the Communist Party, whose leadership is enshrined in China’s constitution. The party is structured as a pyramid. At the lowest level, there are around 92 million party members across the nation, and around 2,200 delegates are elected as representatives to the National Party Congress, convened once every five years. At the Congress, a Central Committee of about 380 members are elected and take up key roles in the central government. Finally, a new Politburo and its standing committee are elected from the Central Committee. These are the organs of government that hold real decision-making power. Currently, there are seven members in the Politburo Standing Committee, representing the apex of power in China. The committee makes decisions through a majority vote. It has been led by party chief Xi Jinping since 2012, who is also the chair of the central military commission.

While on paper the Communist Party operates on the principles of ‘Democratic Centralism’, which allows the party to elect its leadership from the bottom up and discuss and vote on policies in a democratic way, in practice the composition of the Politburo and standing committee is determined through closed-door negotiations. It is unclear to what extent democratic internal debates take place or whether lower-level party members simply go along with top-down directives.

Moreover, the Communist Party has control over all branches of government, including legislative and judiciary institutions. Though there are a number of other smaller political parties present in the National People’s Congress (NPC), the existence of those smaller parties is based on the condition that they accept the Communist Party’s leadership. In effect, they serve as a rubber stamp, offering a nominal diversity of opinions, rather than a real supervisory power or a political opposition. The state council, tasked with enacting national policy and supervising all government departments, is also led by the Chinese premier who is himself a member of the standing committee of the Politburo. Meanwhile, the judiciary is supervised by the party’s central political and legal affairs commission, chaired by a member of the Politburo. However, it is worth noting that although the Chinese state generally works in a way where the power is concentrated at the top, it also consists of many departments and actors with conflicting or competing interests. In addition, lower level bureaucracies are not always in line with the central government, which often creates imbalance and tension in the system.

Pandemic as a case study

The Chinese government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic illuminates the structure of the state in motion and shows how the population interacts with the government. At the start of the pandemic, when its severity was still unknown, local governments’ interests in economic performance and social stability trumped public health concerns, resulting in an extended period of cover-up. The doctors who first detected the virus and alerted others on social media were reprimanded by local police and hospital administrators for sharing false information. Dr. Wen-liang, Li was one of the whistle-blowers who later died from the virus in February 2020, prompting a national outpouring of grief and anger at the government’s handling of the pandemic crisis.

The Chinese government took some measures to enable a certain level of sharing information from the public to improve governance. One example is the health emergency system restructured by the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) after the SARS pandemic in 2003. The system enables individuals to report health incidents to local commissions, but only the national commission and its designated provincial agencies are allowed to make public announcements. As a result, information could flow from the bottom up within the government bureaucracy while still being kept from the public. During the lockdown, there was also a brief period where the government loosened some controls on the media and public expression, which served as a way to collect information and respond to public resentment. However, after the brief loosening of public expression, there followed immersive social media censorship and arrests of ordinary people and citizen journalists. At least 897 people were penalized for online speech about COVID-19, and citizen journalist Zhang Zhan was handed down a four-year prison sentence for her reporting on the pandemic.

China’s security state and people’s daily life

The governance of the state is expressed through the intertwined relational networks that operate at the most molecular level of everyday life. For instance, schools, neighbourhoods, as well as private and public companies, are all required to set up a party branch, which ultimately links back to the formal bureaucracy and is responsible for overseeing and reporting to the upper-level party. In addition, a ‘patriotic education system’ is another important rhetorical device to buttress the ideological legitimacy of the state in people’s daily life.

In the past decade, rapid digitalisation has enabled the government to build security infrastructure to regulate the public sphere and increase surveillance. In the 2000s, the newly available internet enabled people to enjoy a certain level of freedom and autonomy by self-publishing on social media. This led the state to shift from attempting to direct the whole public sphere to managing and controlling discourse. Around 2010, the Chinese government initiated the all-round development of China’s security state; for the first time its domestic security budget surpassed military spending. Over subsequent years, the government implemented a real-name registration system for all mobile phone users and social media accounts, introduced an ID-based ticket booking system for public transport, and constructed an extensive network of CCTV cameras, which was soon connected to facial recognition technology.

In 2013, an internal document entitled ‘Communiqué on the Current State of the Ideological Sphere’ was circulated by the state leadership. The document identified universal values, freedom of the press on the internet, and civil society as major political ‘perils’ that the Party should be on guard against. A year later, the government formed the ‘Central National Security Commission (CNSC)’ in response to the internal and external ‘double pressures’ identified in its documents alongside other factors as a threat to political stability. The CNSC was directly chaired by Xi and developed an ‘overall national security outlook’, which covers politics, territory, military, economy, culture, society, science and technology, information, ecology, nuclear and natural resources.

Around the same time, the crackdown on media and civil society began to intensify. Since 2013, the government has tightened its censorship of mainstream media, arrested investigative reporters and constrained public discussion. In early 2015, a group of five Chinese feminists were detained in Beijing for planning a protest against sexual harassment. In July 2015, the Chinese government launched a nationwide campaign in which it jailed over 100 human rights lawyers and activists and in December, five labour activists were arrested for allegedly ‘disturbing public order’. There have since been numerous waves of repression against every part of civil society. In 2019, when the Anti-Extradition Bill Movement in Hong Kong began, the government conducted a particularly harsh crackdown, arresting more than 10,000 people, and implementing the National Security Law to further break up the movement. For more detail about movements in Hong Kong, see the section ‘Social movements in China’.

Terror capitalism and dispossession of Uyghurs

The Chinese government has constructed a digital enclosure and mass internment system in Xinjiang, the Uyghur autonomous region in northwest China, to control the dissent that has resulted in large part from expanding the capitalist frontier and land dispossession. The technology-enabled entrapment of at least one million ethnic Uighurs illustrates how China’s security state and mass surveillance systems operate.

In the 1990s, the Chinese government expanded its capitalist frontier by encouraging companies and migrants to move to Xinjiang to extract natural resources and extend infrastructure. This led to land dispossession and antagonism between the local population and the new settlers. In the 2010s, with the arrival of 3G networks and digital media, migrant workers in the city used smartphones to find jobs and discuss topics including religion. This not only enabled a revival of Islamic piety and but also allowed for increased connection with the larger Muslim world. Due to the lack of language-recognition technology, voice memos sent in Uygur through social media apps were outside the state-managed public sphere. The combination of these trends made the Chinese state nervous.

Chinese counterterrorism was also inspired by post-9/11 Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) programmes in the United States and Europe and an emerging global discourse around Islamophobia and counter terrorism. As early as 2001 China had started to describe Uyghurs as a population prone to terrorism, but restrictions on the public sphere took off after 2010. In 2013, the Chinese media started to publish numerous stories about cases of terrorism involving Uyghurs attacking Han civilians in Beijing and Kunming, increasing public support for some kind of action to control the Uyghurs.

In 2014, the state declared the ‘Peoples War on Terror’, marking a shift towards preventative policing through surveillance and education systems. The government began to build a new security apparatus to enforce a new wave of racialisation and dispossession of Uyghurs. Apart from the massive deployment of police and lower-level police contractors, the government largely relied on a digital enclosure system to restrict privacy and assert state control of the internet and the Uyghur population. Up to 1,400 private technology firms worked with the Chinese government to develop tools to automate the transcription, translation and detection of Uyghur speech. A ‘counter-terrorism sword’ – software used by police to download all the contents of Xinjiang residents’ phones – was one of the tools the Chinese authorities used extensively to scan people’s digital activities. Through these scans, at least 100,000 people were determined to have committed newly defined criminal activities, such as using a VPN or WhatsApp. Many of them ended up being locked up in internment camps and/or were forced to work in associated factories. In December 2019, the governor of the region announced that all ‘trainees’ had graduated. However, investigations revealed that the government continued to build new detention facilities or renamed ‘training centres’ as ‘detention facilities’, now intended to detain people prior to their trials. As mapped by the Xinjiang Data Project, there are currently around 380 suspected detention facilities in the region. Darren Byler described the process as a shift from mass internment to coerced labour and mass imprisonment.

The mass internment in Xinjiang not only reveals the operation of a security state in China, but also illuminates how terror capitalism in the country is part of global surveillance capitalism. The security apparatus in China is interconnected with American institutions, military programs, and private companies. For example, the US Army has funded joint research with Chinese AI companies which are involved in building the security apparatus in Xinjiang. So, while the Chinese government outsources its policing duties to private and state-owned technology companies to enhance the state’s surveillance capacities, the ‘Public–Private Partnership’ (PPP) creates a space for private industries to expand their market share rapidly and improve their AI capacities through data harvesting and the construction of new analytic tools. Moreover, there is also a racialised component, where difference is accentuated in order to exploit people. In Xinjiang, ethnic Uyghurs have been labelled as terrorists and criminals based on their ethnic status, and their social existence has been systematically undermined through surveillance and indoctrination camps. A similar logic has worked in many places around the world, manipulating the abstract fears of the protected and creating entire groups of ‘suspect communities’ considered to pose a risk.

Webinar participants

- Rebecca Karl, Professor of History at New York University

- Darren Byler, Assistant Professor of International Studies at Simon Fraser University

- Yangyang Cheng, Research Scholar in Law and Fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, where her research focuses on the ethics and governance of science and US–China relations.

- Au Loong-Yu, labour activist

Resources

- Byler, D. (2022) Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- China Media Project: chinamediaproject.org

- Chun, L. (2021) Revolution and Counterrevolution in China: The Paradoxes of Chinese Struggle. London: Verso.

- Gallagher, M.E. (2017) Authoritarian Legality in China: Law, Workers, and the State Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Karl, R.E. (2020) China’s Revolutions in the Modern World: A Brief Interpretive History. New York: Verso.

- Karl, R. (2010) Mao Zedong and China in the 20th-century World: A Concise History Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Loong-Yu, A. (2020) China’s rise: strength and fragility and Hong Kong in revolt: the protest movement and the future of China. London: Pluto Press.

- Manfred E. (2021) Workers and Change in China: Resistance, Repression, Responsiveness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McGregor, R. (2012) The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers. New York: HarperCollins.

- Pan, J. (2020) Welfare for Autocrats: How social assistance cares for its rulers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Saich, T. (2010) Governance and Politics of China (3rd edn). Basingstoke:Palgrave Macmillan.

China’s Economic System

There has been heated debate over the nature of China’s economic system – specifically whether it is capitalist or socialist. This section summarises different views on the development of China’s economic system over three periods of recent history: the socialist period between the 1950s and 1970s, the transition period between the late 1970s and 1990s, and the capitalist period as from the 1990s. This is followed by a summary of several characteristics and trends in China’s current economic system, the crisis it has been facing and its responses.

Socialist period (1950s–mid-1970s)

After the Chinese Communist Party gained power in 1949, it first eliminated private property from the means of production to establish new socialist economic structures. In urban areas, the party nationalised and collectivised industries and established work units based on public ownership. In rural areas, land was redistributed and placed in the hands of villagers’ collectives. But there are diverging views on the character of society in this period and the trends it manifested.

Joel Andreas argues in ‘Disenfranchised: The Rise and Fall of Industrial Citizenship in China’ that, during this period, Chinese workers gained ‘industrial citizenship’, which secured their recognition as legitimate stakeholders in factories through job tenure and extensive membership rights. Although the constraints on autonomous collective action severely limited the potential for workplace democracy, the work structure at the factories was designed to learn from workers’ grievances and the social hierarchy was compressed.

In ‘The Communist Road to Capitalism’, however, Ralf Ruckus contends that, after the abolition of the old class divisions, new ones soon arose between peasants and workers and between different strata of workers. He argues that many overviews of the period are too optimistic and simplistic, and that it is important to examine some of its contradictions. In the 1950s, the system of taxation and unified purchase used to generate resources for the socialist industrialisation programme came at the cost of squeezing peasants’ livelihoods. The workforce was divided into permanent and temporary workers, who were accorded substantially different rights under the hierarchical dual labour system. Moreover, women faced a sexist division of labour as they occupied less skilled positions with lower pay.

Transition to Capitalism (late 1970s–1990)

In ‘Rise of the Red Engineers’, Joel Andreas argues that the Chinese Communist Party’s class-levelling project ended in the late 1970s, after which the party started to restore the cultural and political class hierarchies that had been condemned during the Maoist era. This was done by establishing a more hierarchical education system, as well as through elitist academic and party systems that rewarded cultural and political credentials. In this period, the party retained the socialist economic infrastructure, but merged the cultural and political elites into a new class of ‘technocratic bureaucrats’. These bureaucrats would eventually become the new capitalist class, stimulating the transition to capitalism from the late 1970s.

Others contend that the economic basis for capitalism had already been established in the socialist period. Ralf Ruckus sees the socialist industrial infrastructure, including a disciplined industrial workforce and the patriarchal family structure, as laying important foundations for the new capitalist social relations. In this regard, the market reforms in the late 1970s facilitated the transition to capitalism in the 1990s. For instance, soon after the party officially announced the Economic Reform and Opening policies in 1978, it set up Special Economic Zones (SEZs) to facilitate foreign investment, and restructured the hukou system to enable rural populations to migrate as a cheap labour force in the SEZs. This then triggered new kinds of social struggles arising from rapid urbanisation and proletarianisation.

Capitalist Era (1990s to the present)

From the 1990s, however, commentators and analysts tend to converge. Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 ‘Southern Tour’ marked a clear declaration by the party’s leadership to further transform China’s economy and integrate it into the global capitalist system.

From the mid-1990s, the party accelerated the elimination of full employment and membership rights in the old socialist welfare system, which in cities had been based on the work unit structure. Between 1998 and 2003, around 16 million workers, or 40% of the state sector workforce, were laid off when most of the country’s SOEs were privatised or closed down. The remaining SOEs were amalgamated into modern, profit-driven conglomerates, making the workforce vulnerable to being hired and fired at will to minimise labour costs. In the rural areas, local governments dispossessed many villagers of their land, to be used to developinfrastructure or industrial and commercial projects, totalling over one million illegal land grabs between 1998 and 2005.

After China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, more transnational corporations (TNCs) relocated their global supply chains to the country in pursuit of cheap labour and profits. In 2008, there were 225 million internal migrant workers, most of whom worked in coastal cities in export production. Built on the exploitation of migrant workers, China became the ‘engine of global capitalism’ and the largest destination for FDI. Throughout the 2000s, China enjoyed an unprecedented economic boom with an average of more than 10% annual GDP growth. Production for global markets was central to this boom, with the country becoming the world’s biggest exporter in 2009.

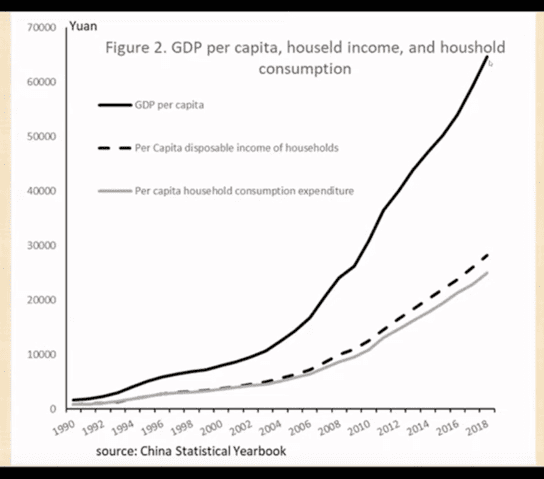

After 2010, however, China’s economic growth has slowed. Although China was able to avoid the worst impact of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis due to its insulation from the global financial system, its export sectors were seriously affected. Throughout 2009 and 2010, the Chinese government introduced massive stimulus programmes, which totalled 4 trillion RMB (USD 586.68 billion), amounting to 12.5% of the country’s 2008 gross domestic product (GDP). Immersive infrastructure projects, such as high-speed railways, roads, and airports, were built with government funding and bank credit. Ho-fung Hung argues that China became burdened with diminishing returns from its continuous credit-funded stimulus projects, as it began to suffer a crisis of over-accumulation and over-leveraging, which worsened throughout the decade. Despite the government’s rhetoric about boosting domestic consumption to respond to over-production, the reality of growing inequality has made this less feasible. In the last 30 years, the growth rate of China’s per capita household consumption expenditure and disposable income has lagged behind its GDP per capita, leading to an increasing gap.

Chart 1: GDP per capita, household income and household consumption between 1990 and 2018

Characteristics of China’s economic system today

China’s current economy is fundamentally capitalist, in the sense that all businesses have to be oriented towards maximising profit. These enterprises co-exist with a strong state that regulates the economy to serve its national goals and ensure social stability.

Yet, while capitalist, China’s economy is also distinct from many others. As Ho-Fung Hung points out, the domination of state enterprises is one distinctive characteristic. The Chinese constitution guarantees the state sector a dominant position in the economy and the party has used SOEs as important levers to direct the economy, playing a major role in domestic and global markets. In the 2021 Global Fortune 500 List, 124 out of 500 are corporations from China and 82 of these 143 are state-owned. The proportion of SOEs’ total revenue compared to private enterprises varies between sectors. In 2018, in strategic industries such as armaments, electricity, and minerals, SOEs compose 85% of all enterprises; in pillar industries, such as construction and electronics, they make up 45%, while in other industries they represent only 15%. Telecommunications and finance are exclusively state-owned, giving the state a continued monopoly of big data and finance.

Ho-Fung Hung also argues that China’s economic slowdown, related to the debt and over-production crisis that has worsened since 2010, has created the context in which the state has launched regulatory crackdowns and is seeking to export capital overseas. Domestically, the government has pushed ahead with the expansion of state sectors at the expense of the private sectors in a situation of ‘economic cannibalism’ that has depressed the overall growth rate. For instance, while the state retains its monopoly in many sectors, its anti-monopoly laws have been disproportionately used against private and foreign enterprises. Internationally, Xi Jinping launched the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI) in 2013 to provide credit to 70 low- and middle-income countries for infrastructure projects to absorb China’s over-accumulation. By 2015, the supply of local currency and loans was still growing while China’s foreign-exchange reserves were stagnant, which led to capital flight, a meltdown of the stock market, and devaluation pressure on the RMB. The state then introduced heavy-handed regulations on the financial market to tighten capital controls. More detail about China’s BRI project is provided in the section ‘China and the World’.

In all of this, it’s important to emphasise the enormous class polarisation and the struggles of ordinary people lying behind economic growth. In the past three decades, China’s explosive capitalist development has largely been built on the massive surplus rural population that supplies cheap labour to the export-oriented economy. In order to keep down the cost of labour, the state has facilitated the exploitation of its workers through overall development strategies in favour of capital. As a result, workers’ basic labour rights are often systematically abused, and their access to social welfare is also structurally limited. More detail about workers’ lives and their struggles is reviewed in other sections, ‘Life in China’ and ‘Social Movement in China’.

Webinar participants

- Ralf Ruckus, editor of gongchao.org

- Joel Andreas, Johns Hopkins UniversityHo-Fung Hung, Johns Hopkins University

Resources

- Andreas, J. (2019) Disenfranchised: The Rise and Fall of Industrial Citizenship in China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chuang, J. (2020) Beneath the China Boom: Labor, Citizenship, and the Making of a Rural Land Market. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.~

- Chuang collective (2021) Social Contagion. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr.

- Hung, Ho-fung (2015) The China Boom: Why China will not rule the world. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Naughton, B. (2018) The Chinese Economy. Adaptation and Growth. (Second Edn). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Roberts, D. (2020) The myth of Chinese Capitalism. London: St. Martin’s Press.

- Ruckus, R. (2021) The Communist Road to Capitalism. How Social Unrest and Containment Have Pushed China’s (R)evolution since 1949. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

- Shih, V.C. (2007) Factions and Finance in China: Elite Conflict and Inflation Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Weber, I. (2021) How China Escaped Shock Therapy: The Market Reform Debate. Abingdon: Routledge.

Social Movements in China

While the Chinese state’s political and economic structural power is characterised by capitalist relations and repressive authoritarianism, the country is still shaped in different ways by power from below. Despite the government’s increasing investment in new forms of technological surveillance and intensifying political arrests, people in China persistently struggle against exploitation, discrimination, and political repression and to secure their rights to a healthy and dignified life. The section explores workers’ struggles and feminist movements in mainland China, as well as the Hong Kong Anti-Extradition Bill movement in 2019.

Labour movement in China

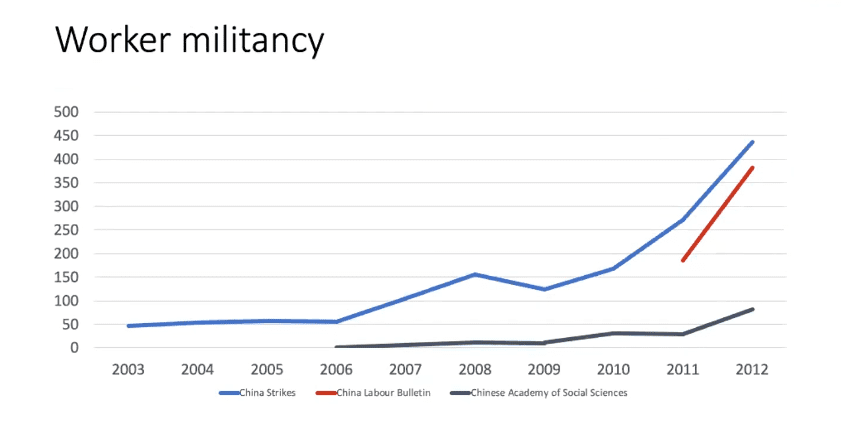

China has a long tradition of labour militancy, stretching back to mobilisation in foreign-controlled ‘treaty ports’ like Shanghai and Guangzhou in the early twentieth century and, from there, to waves of workers’ protests during the Hundred Flowers Movement, as a part of the Cultural Revolution, and during the Tiananmen Square Movement of 1989. Since the beginning of China’s Economic Reform Era, and especially in the early 2000s, there have been numerous strikes and workers have staged protests, petitioned, and rioted in order to push for their demands. Chinese workers have been extraordinarily active. There was a dramatic rise in labour actions during the Hu-Wen administration (2003–2012). There have been fewer since then, which could be interpreted either as a fall in the number of strikes or on reporting on them.

Chart 2: Worker actions between 2003 and 2012 – Source: China Strikes, China Labour Bulletin, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

As noted earlier, at the dawn of the twenty-first century, the working class in China was still divided into two main groups: permanent workers in the old SOE sector and internal rural migrant workers with temporary urban employment. Their different experiences have led to articulating distinct claims. SOE workers experienced privatisation and corporate restructuring, which led to many job losses during China’s Market Reform in the late 1990s and early 2000s. As we have already seen, migrant workers never enjoyed socialist benefits, such as membership rights of their work units, and housing and childcare benefits. On the contrary, they experienced a discriminatory system in the cities, where they were hyper-exploited by factories operated entirely according to a capitalist logic.

C.K. Lee argued in ‘Against the Law: Labour Protests in China’s Rustbelt and Sunbelt’ that the claims of the SOE workers in the 1990s and early 2000s were rooted in their tattered socialist social contract, whereas the migrant workers focused on narrower legal rights. Conversely, Manfred Elfstrom points out that an increasing number of workers also made more assertive demands for higher wages and better social benefits in the later 2000s. For instance, in 2010, thousands of workers stopped Honda automobile plants in Guangzhou which led to the shutdown of the entire supply chain in demand of better wages.

Various actors have given support to these struggles. Workers gain support from social media, from the loose networks of workers from the same home town, and, more recently, from Marxist students. Several years ago, grassroots non-governmental organisations were notable supporters. These were usually based in the industrial zones, where they opened community centres. They later became the target of government crackdowns. Elfstrom argues that NGOs played a complicated role in workers’ struggles. Certainly, some of the criticisms that they focused too much on advocacy and individual legal work as opposed to organising collective actions may be justified, but NGOs also had a more militant side, for instance when they provided advice in strike-making and facilitated informal collective bargaining in the aftermath of work stoppages.

We have noted that China has a single, party-controlled union, ACFTU. Despite its revolutionary history, the union’s main goals today are to maintain peaceful industrial relations and restore normal production if it is disrupted. These goals are inscribed in the country’s Trade Union Law. Very occasionally, the union serves as a fairly neutral mediator between workers and capital, and is a mild internal advocate for new labour legislation on behalf of workers. In most cases, however, the union is merely an arm of management and the local government.

Elfstrom argues that the results of workers’ activism in China have been double-edged: increased responsiveness and increased repression. The struggles of SOE workers have spurred the state to expand the social safety net, and workers’ protests have been credited with encouraging the enactment of a new Labour Contract Law in 2008 and a Social Insurance Law in 2011, providing a more comprehensive legal framework for labour protection. There have also been sporadic pilot experiments to allow elections in enterprise-level unions, and/or sectoral bargaining. It is important to note that these reforms took place in specific localities where independent collective actions were already more frequent. As the union reformers themselves have acknowledged, it was the workers pushing the unions to act, not the other way around. Elfstrom points out that although the repression has been more pronounced under Xi’s administration, with a crackdown on NGO leaders and Marxist students, strikes nevertheless continue and have even expanded to more sectors, like service industries, and the platform economy.

| Year | Timeline of important incidents in the labour movement |

|---|---|

| 1993 | Zhilli Fire in Shenzhen, which led to the death of 81 workers and spurred the enactment of the first Labour Law |

| 1994 | Enactment of the first Labour Law |

| 1995- 2005 | Mass lay-off and impoverishment of SOE workers |

| 2008 | Enactment of Labour Contract Law |

| 2010 | Honda strike in Guangzhou |

| 2010 | Serial Suicides in Foxconn factory |

| 2011 | Enactment of Social Insurance Law |

| 2014 | Strike at Yue Yuen Shoe factory, which involved around 40,000 workers |

| 2015 | Arrests of five labour activists in Guangdong |

| 2016 | Walmart workers launched wildcat strikes across China; thousands of miners went on strike over months of unpaid wages, amid fears of mass layoffs in the government’s SOE restructuring plan |

| 2018 | Workers’ struggle at Jasic factory in Shenzhen and arrests of dozens of workers, their Marxist student supporters and activists |

| 2018 | Nation-wide strike of truck drivers over stagnant pay, high fuel costs and arbitrary fines; Nation-wide strike of crane operators over stagnant pay and poor working condition |

| 2019 | Tech workers started the ‘996 ICU Movement’ against a ‘9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week’ work arrangement |

| 2019 | Arrests of 5 labour activists, who were charged with gathering a crowd to disturb public order |

| 2019 | The arrests of three editors of the labour rights news and advocacy website ‘New Generation’ |

| 2021 | Arrest of delivery worker and organiser Chen Guojiang (Mengzhu), who formed the Delivery Riders Alliance and published short videos about delivery workers’ daily work experiences, calling for them to build solidarity and fight unjust conditions |

#MeToo Movement in China

China’s feminist movement has a long history (see section ‘Life in China’) but in 2018 it connected with the global #MeToo movement, when Xi-xi, Luo shared her allegations of sexual harassment against her former university professors on her social media platform. Her story went viral and encouraged a wave of women to publish their accounts of sexual harassment. To counter the censorship, netizens also invented the hashtag ‘Rice Bunny’ (the Mandarin pronunciation sounds like ‘Me Too’) and used it widely in the online discussion. The #MeToo movement has since expanded to universities, cultural, business and non-profit sectors in China.

The #MeToo Movement responds to the context of the long-term structural suppression of Chinese women and their grievances – as well as a history of women’s mobilisation against this. Women in China continue to face a discriminatory labour market and a society which urges them to have children but fails to provide public childcare support.

In 2011, members of ‘Young Feminist Activism’ started to campaign against discrimination and sexual violence. They organised the ‘Occupy the Men’s Toilets’ campaign to protest over unequal provision of public toilets. They wore wedding dresses covered in red to draw people’s attention to domestic violence. They shaved their hair to address the unequal requirements women face to enrol in university. These eye-catching campaigns caught the attention of Chinese mainstream media, and provoked heated discussions on social media. A few policy changes were also made, including China’s first Anti-domestic Violence Law in 2015. However, in the same year, repression of civil society also intensified: five feminist activists were detained after planning a multi-city protest against sexual harassment on public transport.

In 2018, despite the political climate, the #MeToo Movement expanded and became more decentralised. Countless women continued to post their accounts of sexual harassment online and a handful brought their cases to the courts. In 2018, Zhou Xiaoxuan accused Zhu Jun, a prominent host on state broadcasting, of sexual harassment and drew enormous public attention. After being sued by Zhu for defamation, Zhou counter-sued him for ‘violation of personality rights’, as sexual harassment is not clearly defined in the civil code. In 2020 and 2021, when Zhou’s trials were held, crowds gathered outside the court to show support for her despite police harassment. Although the court eventually ruled that Zhou had tendered insufficient evidence in her sexual harassment case, her action was empowering to many participants in the #MeToo movement. Besides the lawsuit, there have also been various efforts to document and discuss the #MeToo movement in China despite government’s attempt to silence it, including a 2600-page ‘#MeToo in China Archive’ compiled by volunteers, and exhibitions in Guangzhou and Beijing.

Since the #MeToo movement in 2018, a couple of policy initiatives have been introduced. For instance, in 2018, The People’s Procuratorate and the Education Bureau of Hangzhou Xihu District jointly announced the first guidelines to handle sexual harassment cases in schools. In 2021, nine Shenzhen government departments co-published a guidebook to provide a unified standard for sexual harassment policies at schools and workplaces to prevent and punish sexual harassment. In the same year, China’s first-ever Civil Code obliges companies to adopt measures to prevent and respond to sexual harassment in the workplace. However, while the state introduced the new policy initiative, it has also censored the online discussion, arresting and harassing the activists who were part of the grassroots movement that pushed for the changes. A prominent feminist activist, Huang Xueqin, who supported women to come forward with stories of sexual harassment, has been detained since 2021 on the charge of ‘inciting subversion of state power’, and her lawyer’s request to meet with her has been denied.

Hong Kong Movement in 2019

In the summer of 2019, a million people marched in the streets to protest against the Extradition Bill, introduced by the Hong Kong government to enable the extradition of suspects from Hong Kong to mainland China. In so doing, they kicked off the biggest mass movement in Hong Kong’s history.

The government’s refusal to withdraw the bill and increasing police suppression led to a shift in the protesters’ focus, coalescing into Five Demands: complete withdrawal of the Extradition Bill, police accountability, retracting classification of the protests as riots, amnesty for arrested protesters, and universal suffrage for the legislative and chief executive bodies. The protests also expanded to various locations throughout Hong Kong, moving from the financial and political centres to outlying communities. Moreover, due to the intense police crackdown and the government’s refusal to make concessions, protesters began to complement mass demonstrations with more radical tactics, including road blocks, raids of government buildings, and petrol bombs.

The street clashes escalated and reached their peak in mid-November 2019, with street actions taking place every couple of days. In response, the police crackdown and mass arrests also escalated: over a thousand people arrested in a single day as battles took place in two universities. The repression caused immense, social and psychological trauma and led to a decline in this radical street action as protestors perceived little possibility that it could achieve a change.

At the same time, there was a growth on other fronts in the movement, such as unionisation drives, ‘Yellow Economic Circles’ (a network of businesses which openly supported the protests), elections, and community-based organising. These fronts were explored through trial and error. When the pandemic struck at the start of 2020 the networks and solidarity formed by the movement enabled a prompt civil society response. For instance, the network of cross-sector unions became important for workers to express a joint and critical voice to the government’s pandemic policies and facilitated an unprecedent industrial action launched by health workers.

From the start of the Anti-Extradition Movement to early 2021, the Hong Kong police made over 10,200 arrests linked to the movement. In June 2020, the Chinese government escalated the crackdown by bypassing the local legislature to impose a National Security Law (NSL) on Hong Kong. The new law vaguely defined and criminalized activities related to ‘Subversion’, ‘Secession’, ‘Terrorist’ and ‘Collusion with a Foreign Country,’ which could potentially lead to a life sentence. Since the enactment of the law, the National Security Department (NSD) carried out a widespread crackdown on various parts of civil society, including universities, the media, and trade unions, arresting a total of 183 people. In early 2021, 53 activists and legislators were arrested on the grounds of ‘conspiracy to commit subversion’ for taking part in an opposition-organised primary election – speech crimes constitute nearly a third of arrests carried out by the NSD. The same year, dozens of activists from a speech therapists’ trade union and former news outlets were arrested for publishing books and articles under the charges of ‘conspiring to publish seditious publications’, a notorious offence introduced during the colonial period. The arbitrary arrests functioned as an intimidation campaign and led to the mass disbanding of civil society organisations (CSOs) and self-censorship in public discussion.

The crackdown on Hong Kong’s civil society has also had deep repercussions on mainland China. Au Loong-Yu pointed out that Hong Kong’s organisations have a long history of supporting social movements and grassroots initiatives in mainland China, covering a wide spectrum including environmental, labour, and human rights issues. For instance, in the last 30 years, the ‘Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China’ has continuously organized mass vigils to remember the June 4th Tiananmen Square massacre, until it was banned in 2020, with several activists jailed for participating in the illegal gathering. A handful of labour organisations based in Hong Kong have also played a crucial role in supporting groups in mainland China in awareness raising and empowerment of migrant workers. Au Loong-Yu thinks that if the cross-border solidarity and support had continued, we could see a different China, but the government has turned the clock back and cracked down on civil society in Hong Kong and mainland China.

Webinar participants

Au (a pseudonym), an activist from Hong Kong

Manfred Elfstrom, University of British Columbia

Crystal L. (a pseudonym), a Chinese feminist activist

Au Loong Yu, a labour activist

Resources

- China Labour Bulletin. https://clb.org.hk/

- Elfstrom, M. (2021) Workers and Change in China; Resistance, Repression and Responsiveness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, C.K. (2007). Against the Law: Labor Protests in China’s Rustbelt and Sunbelt. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Franceschini, I. and Sorace, C. (eds.) (2022) Proletarian China: A Century of Chinese Labour. London: Verso Books.

- Loong-Yu, A. (2020) Hong Kong in Revolt: The Protest Movement and the Future of China. London: Pluto Press.

- Lu, Z. (2015) Inside China’s Automobile Factories: The Politics of Labor and Worker Resistance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, C.K. (2022) Hong Kong: Global China’s Restive Frontier. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wu, G. Feng, Y. and Lansdowne, H. (2019) Gender Dynamics, Feminist Activism and Social Transformation in China. Abingdon: Routledge.

China and the world

This section provides a contextualised overview of China’s economic and military rise, including the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s overall military capacity, and cross-strait and South China Sea tensions. It also explores reflections from an activist in the Chinese diaspora participating in a transnational social justice movement in a period of heightened US–China geopolitical tensions.

China’s Economic Rise – Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

China’s contemporary economy has been largely integrated with the global economy, but one project above all is seen as representative of China’s global aspirations. Since Xi Jinping unveiled the ‘One Belt One Road Initiative’ in 2013 – later renamed ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI) – to connect the economies of Asia, Europe and Africa with transport and energy infrastructure projects, it has been depicted as a coherent and geopolitical-driven ‘grand strategy’ orchestrated by top Chinese political leaders to dominate the world. Research by Lee Jones and Hong Zhang suggests, however, that BRI was largely determined by ‘multilevel, multi-actor struggles for power and resources’.

Lee Jones argues that profit-seeking SOEs and banks are the dominant actors driving the further internationalisation of the Chinese state. Because SOEs have been facing massive over-capacity, saturated markets, and declining domestic profits, their motives to seek overseas markets became the most significant drive behind the BRI. Political leaders then overlaid diplomatic language on this overseas economic expansion and framed it as a diplomatic ‘win-win’: recipient countries receive investment in projects that other risk-averse competitors are hesitant to back, while China expands its economic globalisation and boosts its international legitimacy. Moreover, the BRI is not an entirely new initiative, but an aggregation and scaling-up of China’s existing overseas economic activities, consolidated to allow foreign governments and consumers to soak up SOEs’ excess capacity and banks’ surplus capital. More discussion about China’s crisis of over-accumulation and overleveraging is reviewed in the section ‘China’s Economic System’.

Hong Zhang categorises five major BRI actors: the central political leadership, government ministries, sub-national governments, enterprises, and social organisations. While the BRI actively mobilises agents across all levels, the central government’s ability to coordinate and oversee these has been weak and ineffectual. Characterised by Jones as a ‘Chinese style regulatory state’, the Chinese government often fails to devise detailed strategies and micro-manage outcomes; conversely, diverse actors may influence, interpret or ignore the broad policy guidelines formulated by the upper echelons. Usually, enterprises are the primary actors, scouting for overseas business opportunities then retrofitting their projects into the country’s overall development strategy and competing for the government’s diplomatic and financial support. This means that ‘the tail wags the dog’, with many uncoordinated and poorly thought-through projects being approved. Moreover, as Hong Zhang’s research shows, SOEs are often powerful economic actors in their own right, and are to some extent independent of the government’s ‘financial power’.

China is now a major international investor and creditor, and its involvement in development financing is also noteworthy. Over the 2000–2014 period, China’s overall provision of development finance totalled US $354 billion, only US $40 billion behind the US. However, while China’s share of foreign governments’ debt has risen substantially, its debt ownership is still relatively small compared to private lenders overall and lags well behind the established multilateral lenders. As of 2022, China is the dominant lender in only 17 debt-distressed states worldwide.

Chinese market dominance in overseas infrastructure projects, particularly in Africa and Asia, is unassailable, with nearly 1,000 projects totalling $170 billion dollars over the 2013–2021 period. Further information on some of these projects can be found on ‘The People’s Map of Global China’, a bottom-up, collaborative initiative documenting infrastructure and other projects financed and/or built by Chinese entities worldwide. Some of these projects are facing great challenges or already failing, which Jones interpreted as a reflection of the shortcomings of Chinese-style regulatory governance and recipient states’ economic unsustainability, rather than the success of Beijing’s ‘debt trap diplomacy’.

Low transparency in governance and in engagements with the local community are common problems, which have led to significant ‘blowback’ for China from recipient countries. For instance, the land-grabs and displacements associated with several BRI projects in Cambodia and Sri Lanka have caused serious local unrest. In recent years, due to rising concern about the potential risks and backlash, an increasing number of recipient countries are suspending (Sierra Leone) or scaling back (Myanmar, Malaysia) major planned BRI projects. The BRI therefore does not only strengthen China’s ties with recipients, but may also generate local and inter-state discord, undermining Beijing’s broader foreign policy goals.

China’s Military Rise – Cross-strait and South China Sea Tensions

There is no doubt that China is modernising and expanding its military capacities, although Walden Bello argues that this is largely limited to its own region rather than being a global phenomenon. Key indicators show that China’s military capacity remains largely inferior to other global powers, specifically the US. In terms of nuclear weapons, it is estimated that China has 350 nuclear warheads while the US has 5,600; the US has 800 military bases in 177 countries (out of a total of 195) while China only has one military base in Africa, and an overseas military presence in a few sites in Tajikistan and artificial islands in Asia. China only has two aircraft carriers based on an antiquated design while the U.S. has 11 of the total 43 that exist in the world today.

However, the South China Sea (SCS) dispute and cross-strait tension with Taiwan are two major flash points for intensifying geopolitical tensions. The South China Sea (SCS) is a strategic link between the Pacific and Indian Ocean, which is not only an important trade route but also rich in oil, natural gas, and fish. It has been a point of contention in the disputed territorial claims among Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam. In the past decade, China has carried out increasingly aggressive military activities in the region by building artificial islands for military bases, exploring for natural resources, and violating the rights of neighbouring countries. Walden Bello points out that an important factor in the SCS is US forward-deployed military presence in the region. Furthermore, China is surrounded by around 50 US military bases from Northern Japan to the island of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, the South China Sea has also been controlled by the US 7th Fleet with its carrier taskforces, surface ships, nuclear-armed attack capacity, strategic submarines, and provocative air reconnaissance. Bello argues that, while the US and China are jostling for power in the region, this has created an explosive situation for the entire region, and although China’s moves might be understandable in its geopolitical tension with the US, this is no justification for them.

Taiwan is only 160 km off China’s coast, and its political status has been contested. While Beijing claims Taiwan is part of China, Taiwan enjoys de facto autonomy with its own elected president and independent political system. Although China’s military aggression is not new to Taiwan, in the past few years, Chinese warplanes have crossed the median line of the Taiwan Strait at a historically high level. However, although the western media plays up the military threats, survey results show that the Taiwanese are aware of these but are not necessarily worried about the prospects of an immediate military conflict.

Brian Hioe lays out some political and economic context to take into account when assessing the possibility of a cross-strait conflict. Despite the significant difference in military capacity between China and Taiwan, occupation of Taiwan would not be as easy as some observers might assume. Militarily, Hioe argues that China would face a severe death toll from a beachhead invasion, and currently China still lacks the ‘lift capacity’ to send troops for a long-term occupation of Taiwan. Economically, the world’s dependence on China and significantly on Taiwan would also be a decisive factor. As Taiwan produces more than half of the world’s semiconductors, used in all kinds of electronic devices from missiles to mobile phones, China would want to ensure minimal disruption and preserve know-how and infrastructure in Taiwan. This has led China to follow a multi-pronged strategy: not just intimidation campaigns and psychological warfare, but also economic and political co-optation as a strategy towards unification. So, China facilitates a class of cross-strait elites to encourage economic integration and supports KMT, the Chinese National Party, as its domestic proxy to attempt to take over Taiwan through electoral means. Similar to the regional tension in the South China Sea, Hioe points out that Taiwan is caught between the US and China. US diplomatic visits and gestures regarding Taiwan often lead to a response of China’s military aggression in a tit-for-tat escalation.

Diaspora activists’ experiences in the heightened US–China tension

May Wu is a social justice organiser who works with Chinese students and activists in the US and internationally. She shared her personal experiences of participating in transnational social justice movement in the US, which also sheds light on the struggles of the Chinese diaspora in the heightened US–China tension and her insights on reimagining international solidarity.

With the population of Chinese students in the US totalling more than 300,000, May underlines the importance of mobilising them while the liberal environment gives them opportunities to engage in social movements. However, as Mengyang Zhao argues in his article ‘Chinese Diaspora Activism and the Future of International Solidarity’, diaspora activists often suffer the ‘triple penalty’ of simultaneously being activists, immigrants in their countries of residence, and activists in their home countries. In the context in the US, the Chinese state is aggressively tightening its grip on diaspora activists, and puts them under extensive surveillance and scrutiny. At the same time, the worsening US–China relationship, Trump’s rise, and anti-Asian hate crimes following the pandemic outbreak has caught diaspora activists between two state actors and growing hostility in the US. For instance, May noted that when Chinese students and activists participated in the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in the US, their actions were viewed as evidence of having been brainwashed by ‘western liberal values’ among the mainstream Chinese public, and perceived by some US audiences as an intervention by Chinese communist spies sent to sabotage US domestic politics.

It is important to move beyond the common stereotype that Chinese diaspora activists are only ‘dissidents against Chinese government in liberal democratic countries’. Diaspora activists have huge amounts to contribute to social movement in their countries of residence practically and intellectually. During the BLM movement, in solidarity, some Chinese students joined rallies, created content and workshops about the topics, and participated in initiatives led by people of colour. Some also organised fellow students to contact Chinatown vendors to explain the cause of the movement. May argues that overseas Chinese students have a long history of transnational social movement organising in the US, and their participation in activism today is a living example of this transnational identity, building bridges between Chinese students, resident and home communities, and with other diaspora activists and local movements.

Webinar participants

- Brian Hioe, activist in Taiwan, editor of New Bloom Magazine

- Lee Jones, Queen Mary University London

- Hong Zhang, John Hopkins University and co-editor of the People’s Map of Global China (https://thepeoplesmap.net)

- Walden Bello, Focus on the Global South

Resources

- Bello, W. (2019) China: An Imperial Power in the Image of the West? Bangkok: Focus on the Global South.

- Dreher, A., Fuchs, A., Parks, B., Strange, A. and Tierney, M.J. (2022) Banking on Beijing: The Aims and Impacts of China’s Overseas Development Program. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Global China Pulse: https://thepeoplesmap.net/globalchinapulse/global-china-pulse-1-2022/

- Jones, L. and Hameiri, S. (2021) Fractured China: How State Transformation is Shaping China’s Rise. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jones, L. and Hameiri, S. (2020) Debunking the Myth of ‘Debt Trap Diplomacy’: How Recipient Countries Shape China’s Belt and Road Initiative. London: Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2020/08/debunking-myth-debt-trap-diplomacy

- Lee, C.K. (2017) The Specter of Global China: Politics, Labor, And Foreign Investment in Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- New Bloom: https://newbloommag.net/

- Pettis, M.K. (2020) Trade Wars are Class Wars. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Reilly, J. (2021) Orchestration: China’s Economic Statecraft Across Asia and Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ye, M. (2020) The Belt Road and Beyond: State-Mobilized Globalization in China: 1998–2018. New York: Cambridge University Press.

China and the planet

The climate crisis affects the entire globe. Addressing it depends on international collaboration and collective action coordinated across the planet. This section examines China’s contribution to the global climate crisis, and the progress and shortcomings of its current policies. China has long been at the centre of the debate over this crisis, but much analysis often fails to understand its position in the global economy, the role of social movements in the country, and the possibilities for international climate cooperation.

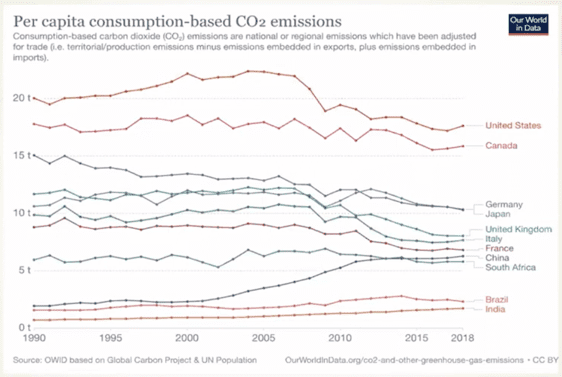

Economic development and the energy model

China’s economic model and its position in global supply chains have significant implications for its energy model. China’s contribution to global emissions is a relatively recent phenomenon, coinciding with its spectacular economic growth and its emergence as ‘the factory of the world’. China’s export-led and infrastructure-building economic model, as well as its coal-rich energy resources, established an energy system that is highly dependent on coal, which has led to high carbon intensity given its economic outputs and also created enormous greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. China’s carbon emissions started to take off in the early 2000s and escalated until 2012. In 2006, China overtook the US as the largest annual contributor to global carbon emissions in absolute terms, although US remains responsible for the largest share of historical emissions, with some 20% of the global total as of 2021.