Public service economics and the growing rejection of privatisation in the UK

April 22, 2018 | David Hall

Visiting professor, Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU)

University of Greenwich

AEPF Manila February 2018

1. Economics of public services

Public spending and public services are vital for social development. However, politicians and media and mainstream economists consistently say that they are an unaffordable luxury, which damages the market economy, because taxation is a drain on private enterprise, because universal public services distort the market, and because the public sector is less efficient than the private sector.

But public spending is not an economic liability. Far from being a burden on the economy, public spending has had a consistent positive effect for over a century. This positive link works in developing countries as well as high income countries. Public spending supports economic growth through investment in infrastructure, through supporting an educated and healthy workforce, through redistributing income to increase the spending power of poorer consumers, providing insurance against risks, providing direct support for industry, including through technological innovation, and increasing efficiency by taking on these functions.

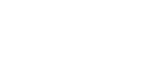

Chart 1. Government spending as % of GDP 1870–2012, high income countries

Sources: see note [1]

Public spending supports employment, in both high income and developing countries, through: direct employment of public service workers; indirect employment of workers, by contractors supplying outsourced goods and services; employment of workers on infrastructure projects; extra demand and jobs from the spending of the wages of these workers and also of recipients of social security benefits (the ‘multiplier effect’); subsidies to support employment by private companies, or by providing employment guarantees; providing formal jobs with decent pay and conditions; government procurement is used to require ‘fair wages’ from private contractors, to reduce gender and ethnic discrimination, and strengthen formal employment of local workers. The combined effect of these mechanisms is to support half the formal jobs in the world.

The supporters of austerity programmes argue that government debt damages economic growth, but there is no evidence to support this – a Harvard University paper which claimed to find a connection has been discredited. Government borrowing is a key economic instrument for driving economic activity, and is much cheaper than borrowing by private companies, which have to pay much higher interest rates. Privatisation and PPPs are unnecessary, costly and damaging ways of raising money.

The purpose of public spending and public services is to achieve public objectives. These objectives include, for example, ensuring universal education and universal access to healthcare; environmental objectives such as the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and management of waste; and economic objectives such as full employment. In a wide range of areas, these objectives are most effectively and efficiently achieved through public spending and public services. This section examines three policy areas where public spending and public services are key – healthcare; housing; and climate change.

Government revenues consist of taxes of various kinds and income from other sources. Countries with higher GDP have higher levels of taxation, so an increasing level of taxation is a key part of economic development. The total amount needs to be sufficient to pay for spending on public services and social security, and the burden of taxation should be fairly distributed. But neoliberal policies have attempted to reduce taxation, and have shifted the tax burden away from the rich, and corporate profits, on to ordinary people. All countries could increase their revenues substantially, just by increasing taxes on high incomes, property and corporate profits. This requires action to strengthen tax collection systems, and to deal with tax avoidance and the use of tax havens.

Changing current policies depends on political activity. Market mechanisms do not deliver the level of public services which countries need. The decisions which drive the development of public spending, or the imposition of austerity, are the outcome of political processes at national and international level.

2. Public services and equality

Equality is usually discussed in terms of people’s income, or the inequality suffered through systematic ethnic or gender discrimination. It is well recognised that public spending redistributes money income through social security benefits, but public services like healthcare, public education, child care, care for the elderly, and public housing also have a powerful redistributive effect, because they are equally available to everyone. Infrastructure like water, sanitation, electricity, roads and telecoms also improve equality because they make it possible for everyone to improve their livelihoods by using these services. As a result, cuts in spending on services have a disproportionate impact on households on lower incomes.

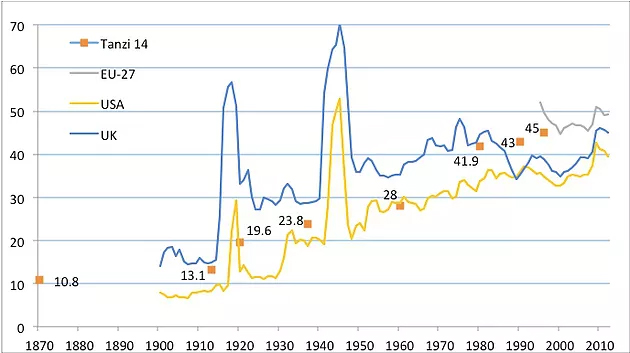

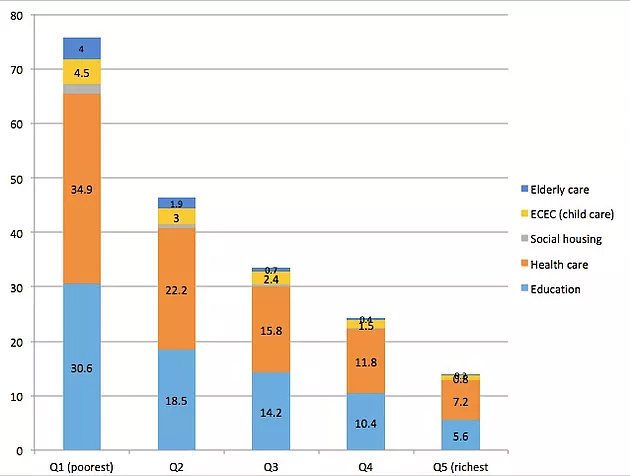

Recent studies in all high-income countries, and in 6 major Latin American countries, have shown that public services are relatively progressive in every country – the poor get a much higher proportion of the benefit of public services than they do of market income. And the value of these services, and the impact on equality, is at least as great as the impact of social security.

In OECD countries public services are equivalent to an extra 76% of the disposable cash income of the poorest 20%. In Latin America, public services have the same effect, making a greater impact on equality than social security benefits. Infrastructure for electricity, water and other services not only increases access for all, but improves employment opportunities, especially for women.

In addition, services such as child care, care for older people and education have a big impact on gender and ethnic equality, because they allow more women to get paid employment, and can be used to provide decent employment and career prospects for members of ethnic groups which have suffered discrimination. Other spending on public services takes the form of buying goods and services from private companies, and this too can be used to improve equality by making contracts conditional on positive discrimination in favour of women.

And through employing more people on better pay and conditions, with less differential between top and bottom, public services also improve income equality.

Chart 2. Value of public services as % of disposable income, 27 OECD countries

Source: calculated from Verbist et al p.35

Chart 3. Impact on inequality of taxes and benefits, and public services (Gini coefficient, 6 Latin American countries)

Source: Lustig et al 2012

3. The illusion of PPPs

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) are used as a way of raising money for expensive infrastructure projects through the private sector, to avoid any apparent increase in public borrowing. The private partner in the PPP raises the money, so the government does not have to – and the bridge, or tunnel, or motorway, or railway, or school or hospital – still gets built. PPPs are actively promoted by a range of international institutions and governments, including the World Bank, G20, EU and donors countries.

The first fundamental problem is the illusion that PPPs bring in private money to pay for the infrastructure, so the state can spend its money on something else. But the opposite is true. The great majority of PPPs rely on a stream of income from payments by government (for the hospital, school, railway, etc.) – i.e. public spending (with the exception of true concessions, where the private company makes all the investment “at its own risk”, expecting to get the necessary income from payments made by consumers (e.g. water charges or road tolls). PPPs do not supplement public spending – they absorb it.

The second problem is that governments can always borrow more cheaply than companies, so raising money through PPPs is always the worse option. This has been stated very clearly by the IMF: “… private sector borrowing generally costs more than government borrowing … This being the case, when PPPs result in private borrowing being substituted for government borrowing, financing costs will in most cases rise …”. (IMF 2004A, IMF 2004B) In 2011 a representative of the UK private companies involved in PPPs estimated that the average extra cost of private sector capital over conventional borrowing had been 2.2 per cent a year. The Financial Times calculated that this means that the UK taxpayer: “is paying well over £20bn in extra borrowing costs – the equivalent of more than 40 sizeable new hospitals – for the 700 projects that successive governments have acquired under the private finance initiative….”

Finally, when PPPs are used to finance public investment, the private investors naturally seek to protect themselves against risks and uncertainty. Governments therefore usually provide some form of guarantee, or agreement to carry risks, to provide greater security for the private investor. But, as the IMF again notes: “… resort[ing] to guarantees to secure private financing can expose the government to hidden and often higher costs than traditional public financing”. The further irony is that, since the financial crisis, state banks and institutions are actually lending money to PPPs, in order to borrow it back from them.

Despite the massive promotion effort, PPPs struggle to provide more than a tiny portion of the infrastructure investment in the world. Public finance remains the overwhelmingly predominant model worldwide, providing for well over 90% of infrastructure investment.

And many PPPs have been expensive failures. In the UK, the world leader in using PPPs, all the transport PPPs in London have been terminated – representing over 25% of the value of all the PPPs in the UK. The result has been a considerable saving in the cost of borrowing and in efficiency. (PSIRU 2014B)

4. Potential for more tax revenues

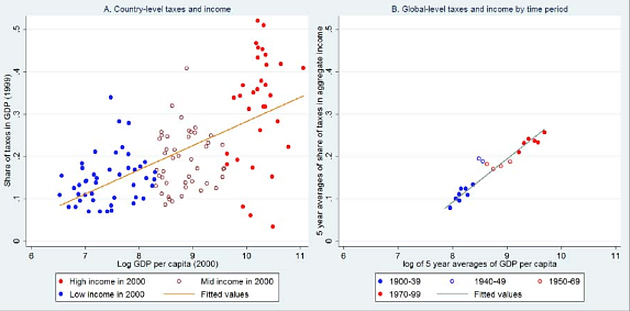

Taxation is not a burden but an essential part of economic , social and political development. As economies grow, tax revenues rise as a proportion of GDP:. “rich countries collect a much larger share of their income in taxes than do poor countries”, as the first chart shows. Higher tax revenues are a crucial part of development: “the power to tax lies at the heart of state development” – the second chart shows how the level of taxation has grown steadily for the last 100 years. (Besley and Persson 2013)

Chart 4. Higher GDP means higher taxation

Source: Besley and Persson 2013

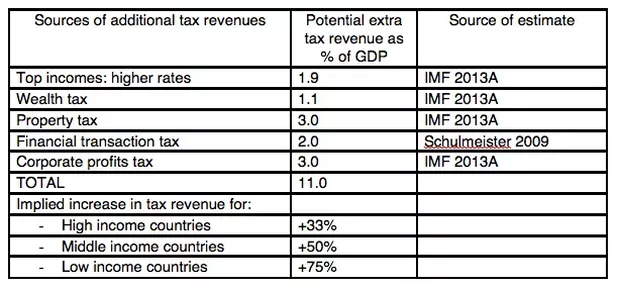

Far more tax revenues can and should be collected from taxes on high incomes, wealth, company profits, financial transactions, and from land and property. The table below shows estimates by the IMF and others of the potential extra revenues from some of these sources.

- these add up to potential extra revenue equivalent to 11% of GDP.

- they would represent a huge increase in tax revenues: an increase of 33% in high income countries, an extra 50% in middle income countries, and an extra 70% in low income countries.

- the IMF estimates that the government debt of all countries could be restored to the levels of 2007 by a general tax of 10% on private wealth (IMF 2013A)

Chart 5. Potential extra revenues from taxing the rich and companies

Financial transactions tax

The proposal for a general tax on financial transactions is often called a ‘Tobin tax’ after the Nobel-prize-winning economist who advocated it as a way of deterring such transactions, to protect currencies from the volatility of speculative inflows and outflows. Many countries operate similar taxes successfully: China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Italy, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Switzerland, Taiwan and the U.K. all tax the purchase and/or sale of company shares. If applied globally, a financial transactions tax could raise over USD $1trillion per year, or 2% of global GDP, even at a rate of 0.01%. A more limited currency transaction tax could raise between USD $25–33billion per year. (Taskforce 2010) Political support for the idea, in principle, has been growing for some years. In 2013 the EU proposed a directive to provide a framework for financial transaction taxes in Europe. (EU 2013, Thornton Matheson 2011)

Property and land taxes

The advantages of a property tax are that it is fair, hard to avoid, and impacts on people with assets whose value is increased by public services and infrastructure. There is wide variation between countries in taxes on property, and so considerable potential for collecting more from these sources.

A land tax is even broader, because it taxes all land, not just the buildings on it. It also taxes the value that landowners gain from economic growth and rises in property prices. Hong Kong uses a land tax to raise 38% of its revenues. A land tax has been supported by a wide range of people in the last 250 years, including Adam Smith, Tom Paine and Winston Churchill, who argued that infrastructure increases land values, but the landowner: “renders no service to the community, he contributes nothing to the general welfare, he contributes nothing to the process from which his own enrichment is derived.” (McLean 2004)

5. The remarkable turnaround in the UK

The underlying reasons for the opposition to privatisation in the UK are economic, as in other countries. People have experienced higher water and energy and rail prices, worse service, loss of jobs and pay, and loss of accountability, while the companies make large profits. Opinion polls suggested that the UK public never supported many of the privatisations, but since the 1990s, when the Labour party decided to drop opposition to privatisation, there has been no political force expressing that opposition.

The key factors in the change have been political. A new campaign group was launched in 2013, called We Own It, focussed simply on the demand to reverse all forms of privatisation – the sales of the water and electricity and rail companies, the various PPPs/PFIs that have been set up in the UK, and the whole area of outsourcing. This was the first anti-privatisation campaign in UK since the early 1990s, and it gained a lot of support from the public and significant publicity.

Then in 2015 Jeremy Corbyn, a longstanding left-wing MP, was elected leader of the Labour party, by a large majority. He was re-elected in 2016, again with a large majority, and the party’s membership grew to 500,000, making it the largest political party in Europe. In May 2017 a general election was called, and Labour produced a manifesto which included a commitment to bring back public ownership of water, energy and rail companies. These commitments played a large part in winning the support of over 40% of voters, and the Conservative government was left with no overall majority. The election made clear that ending privatisation was extremely popular.

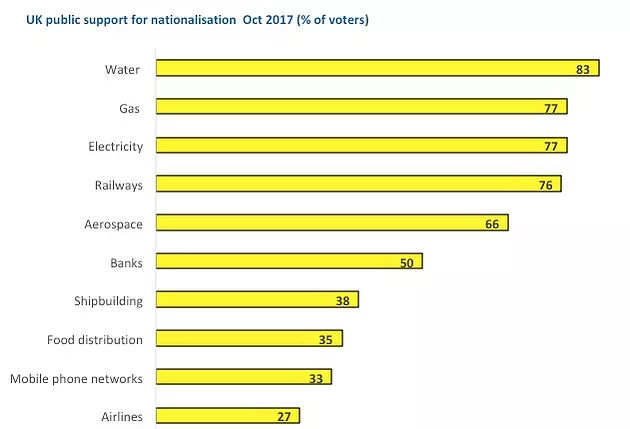

Since the election, this political process has accelerated. In October 2017 a survey conducted by a right-wing research group found that over three-quarters of the electorate wanted public ownership of water, electricity, gas and rail, and at least half wanted public ownership of the aerospace industry and the banks.

Chart 6. UK public support for public ownership, by sector, October 2017

Source: Legatum Institute Oct 2017 Public opinion in the post-Brexit era. www.li.com

At its annual conference in September 2017, the Labour party not only reiterated and maintained its commitment to public ownership of utilities, but also adopted radical policies in relation to outsourcing and PPPs. On outsourcing, the new policy is to hold a comprehensive review of all work outsourced by local and central government and health authorities, and introduce a new statutory rule that all work must be done inhouse by default unless a special case is made under strict criteria.

On PPPs, the party policy is now that there will be no new PPPs created, and that all existing PPPs will be nationalised. The party is extending this approach to its policy on international development, so that a Labour government will withdraw the UK’s support from policies encouraging the use of PPPs in developing countries.

At the same time, the media, and private capital, has been forced to re-examine the problems of privatisation. Surprisingly, the Financial Times has published some of the strongest and most detailed critiques of privatisation and PPPs. Credit rating agency Moodys produced a briefing which agreed that Labour could legally nationalise the water and energy sectors, even without paying full market value in compensation. Investors now take nationalisation as a serious possibility, and the price of the shares of water companies on the London stock exchange has fallen by 25% or more Since May 2017, when Labour’s manifesto was first published. A report on the energy sector, commissioned by the Conservative government from a neoliberal economist, Dieter Helm, surprisingly recommended public ownership of the electricity transmission and distribution grids. A major new report on outsourcing has also undermined.

The process has been reinforced by further problems with privatisation, including the bankruptcy of Carillion, one of the major multinationals involved in PPPs in the UK (and elsewhere), and financial problems with another major PPP operator, Capita.

Chart 7. Financial Times articles, September 2017